Pityriasis rosea is a common papulosquamous disorder. However, its etiology and pathogenesis remain unclear.

ObjectiveWe investigate the types of inflammatory cells infiltrating the lesional skin of pityriasis rosea and demonstrate whether T-cell-mediated immunity is involved in the pathogenesis of this condition or not.

MethodsThe biopsies were taken from the lesional skin of 35 cases of patients diagnosed with pityriasis rosea. The specimens were prepared in paraffin sections, then submitted to routine immunohistochemistry procedures using monoclonal antibodies directed against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20 and CD45RO and horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human antibodies. The positive sections were determined by the ratio and staining intensity of positive inflammatory cells.

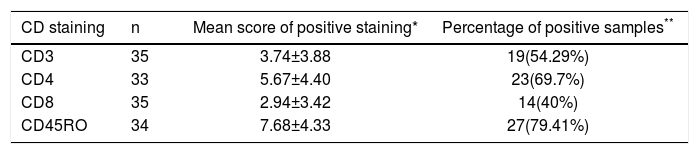

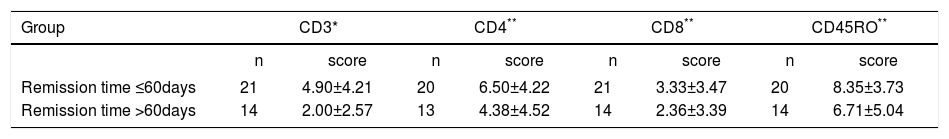

ResultsThe mean score of positive CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD45RO staining was respectively 3.74±3.88, 5.67±4.40, 2.94±3.42 and 7.68±4.33 in these pityriasis rosea patients (P<0.001). The percentage of positive staining was 54.29% (19/35), 69.7% (23/33), 40% (14/35) and 79.41% (27/34) (P<0.05). However, the staining of CD20 was negative in all samples. The mean score of CD3 staining in patients with time for remission ≤60 days (4.90±4.21) was higher than that in patients with time for remission >60 days (2.00±2.5) (P<0.05), whereas no statistical difference in the mean score of CD4, CD8 and CD45RO staining was observed.

Study limitationsThe sample size and the selected monoclonal antibody are limited, so the results reflect only part of the cellular immunity in the pathogenesis of pityriasis rosea.

ConclusionOur findings support a predominantly T-cell mediated immunity in the development of pityriasis rosea.

Pityriasis rosea (PR) is a common inflammatory papulosquamous disorder. The rash usually resolves within 6-8 weeks; however, the disease can last for a longer time in some patients. The persistence of disease is associated with the systemic reactivation of human herpes virus 6 (HHV-6) and human herpes virus 7 (HHV-7).1 Although it is self-limited, this disorder has some unfavorable influences on most patients. Up to now, its etiology and pathogenesis have not been well elucidated. Previously, we found the level of interferon-γ was decreased in the sera of PR patients.2 There are very few studies about the immunohistochemical features of PR. Therefore, we performed immunohistochemical staining of the inflammatory cells infiltrating the skin lesions to demonstrate the role of T-cell-mediated immunity in the development of PR.

MethodsThirty-five patients with PR (19 males and 16 females) were included in the study. Eight cases were of patients with <1 week duration, and 27 cases were of patients with ≥1 week duration. The mean age of these patients was 29.06±9.43 years (range 17-53 years old). At the time of diagnosis, the mean duration of disease was 29.03 days (range 1-180 days). The mean time for remission of disease was 67.54±44.86 days (range 21-240 days). Biopsies were taken from one of the secondary lesions after each patient gave their informed consent. All skin samples were fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, then submitted to routine immunohistochemistry procedures using monoclonal antibody directed against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD20 and CD45RO and horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-human antibodies. The positive sections were determined by the ratio and staining intensity of positive inflammatory cells. The score of staining intensity was rated 0 (negative), 1 (faint yellow), 2 (brown) and 3 (tan-colored), while the score of the ratio of positive cells was rated 0 (negative), 1 (<10%), 2 (10%-25%), 3 (26%-50%), 4 (51%-75%) and 5 (75%-100%). The multiplication of these two scores is the final score. The staining of the section was considered positive if the final score was ≥3. The mean score and the percentage of positive staining were compared for CD3, CD4, CD8 and CD45RO using analysis of variance and Pearson Chi-square test, respectively. The mean scores of CD3, CD4, CD8 and CD45RO staining was compared between two groups using Student’s test. Number of Research Ethics Committee: 20180318.

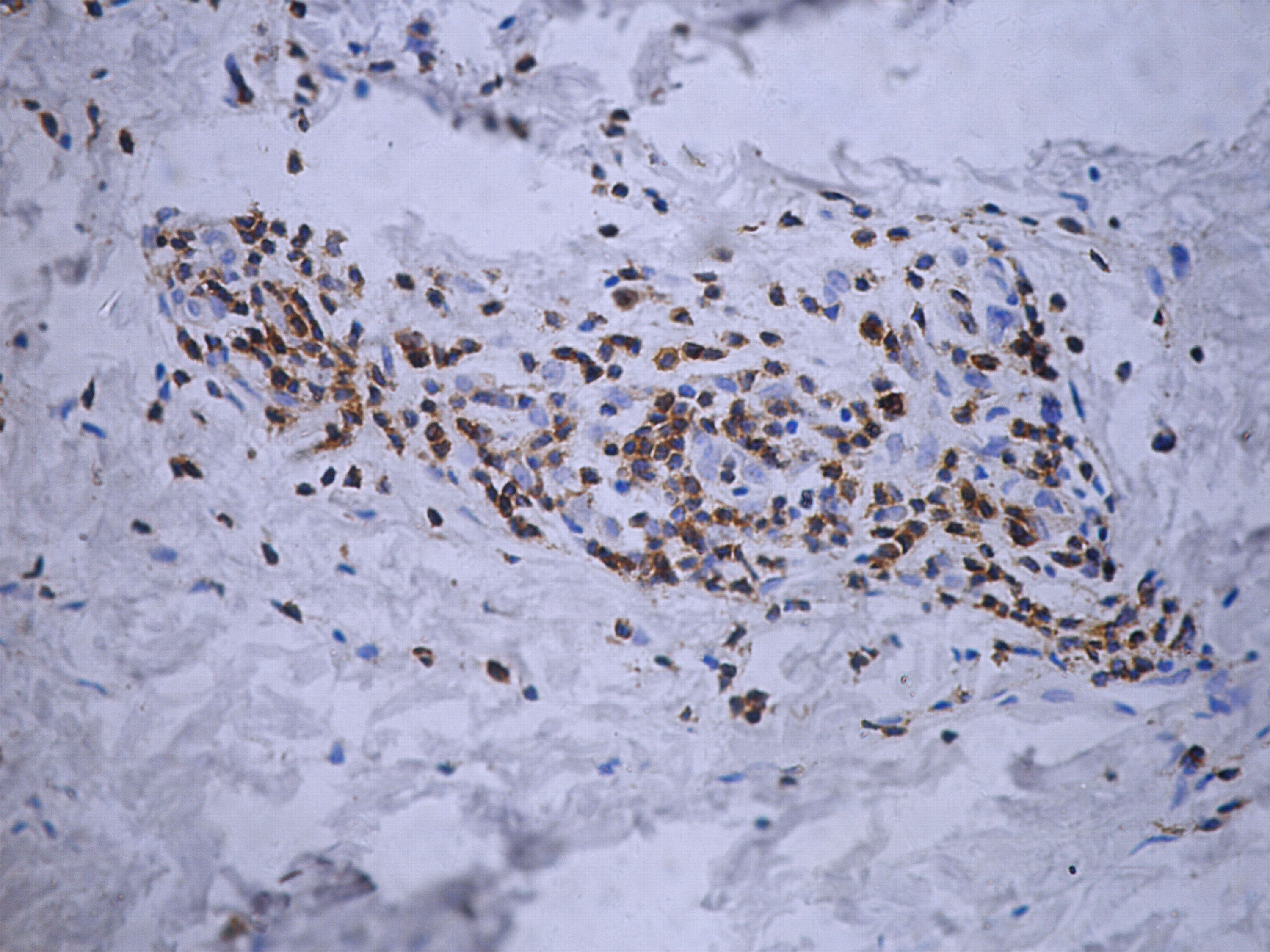

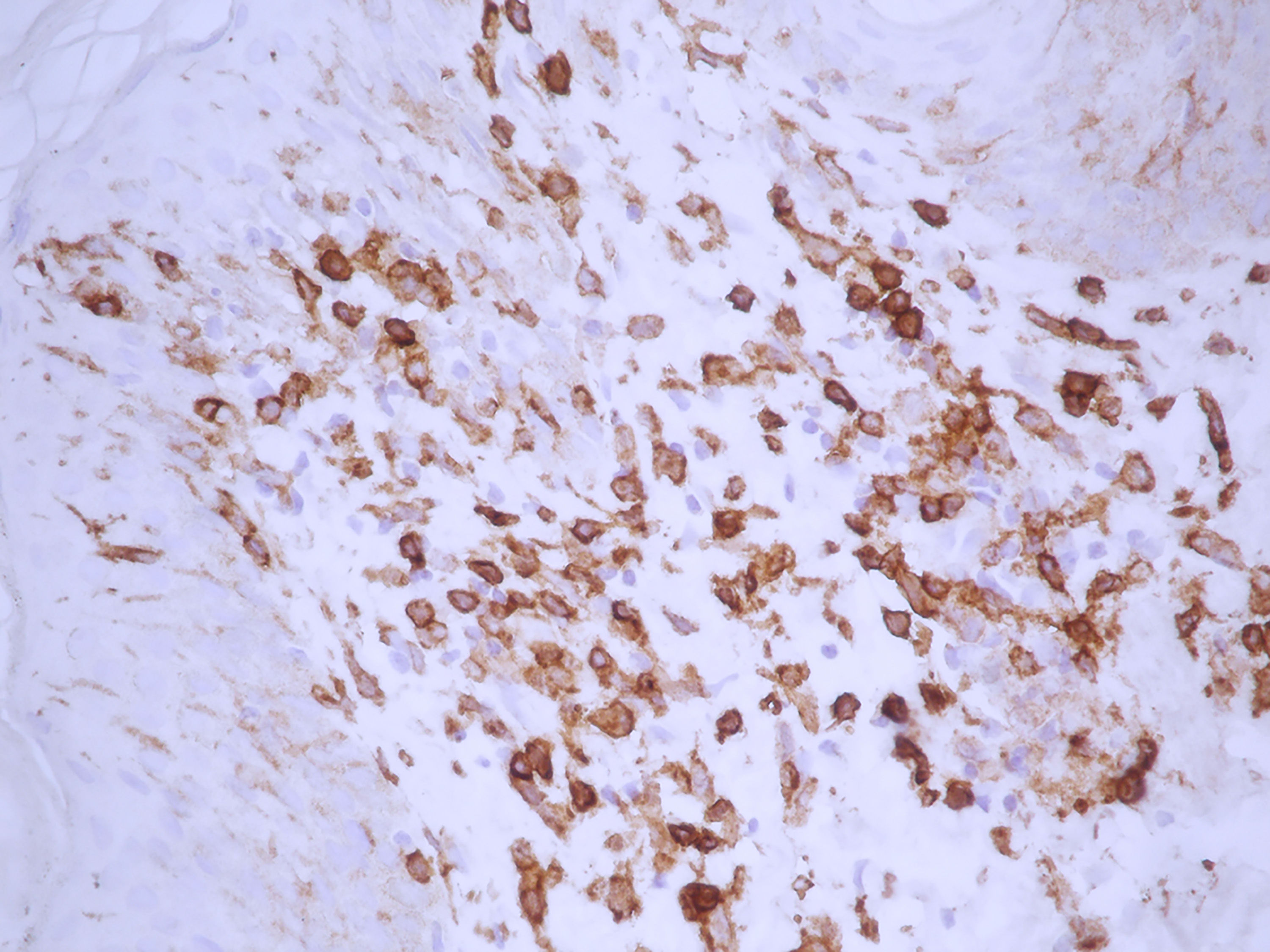

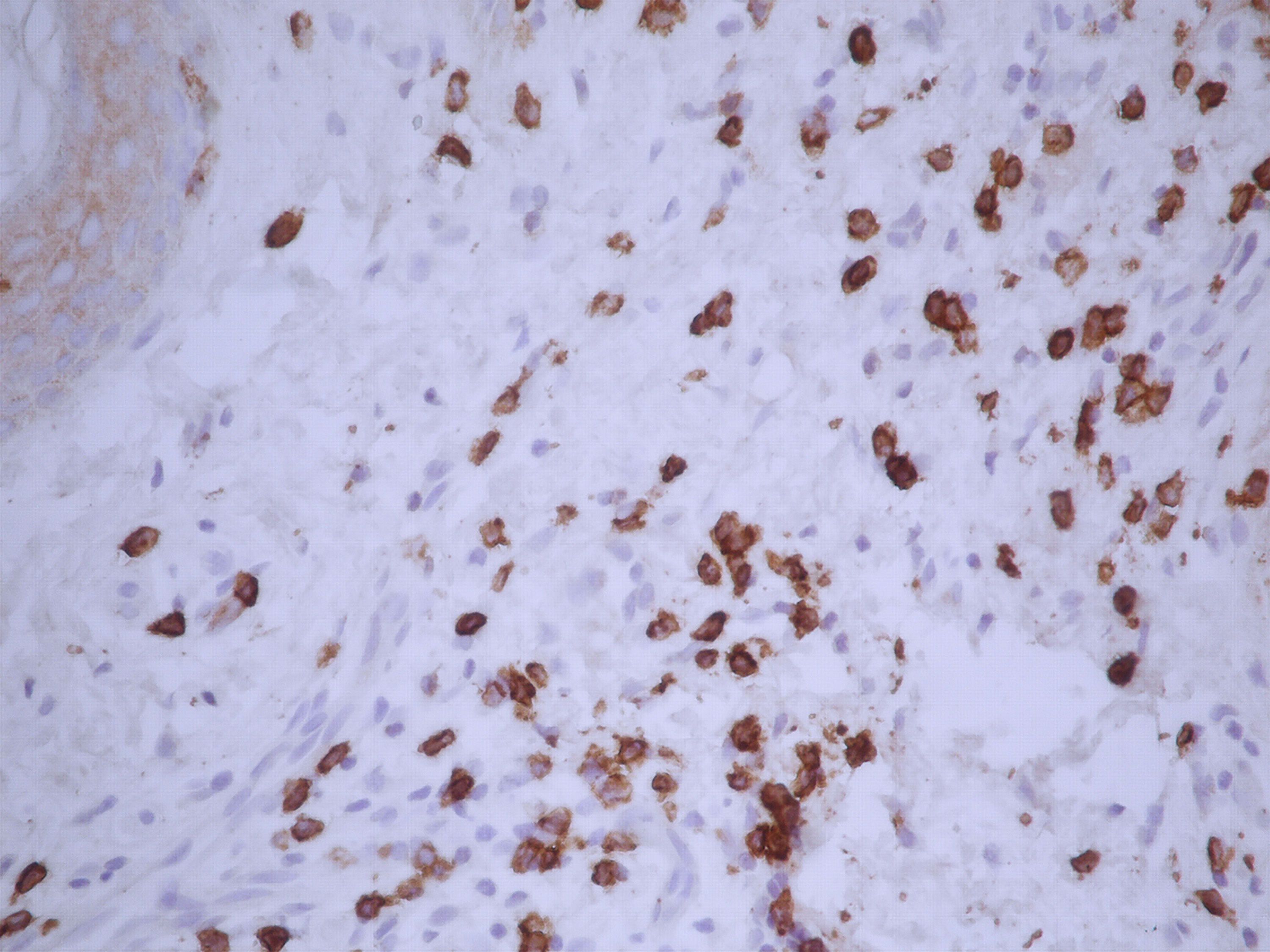

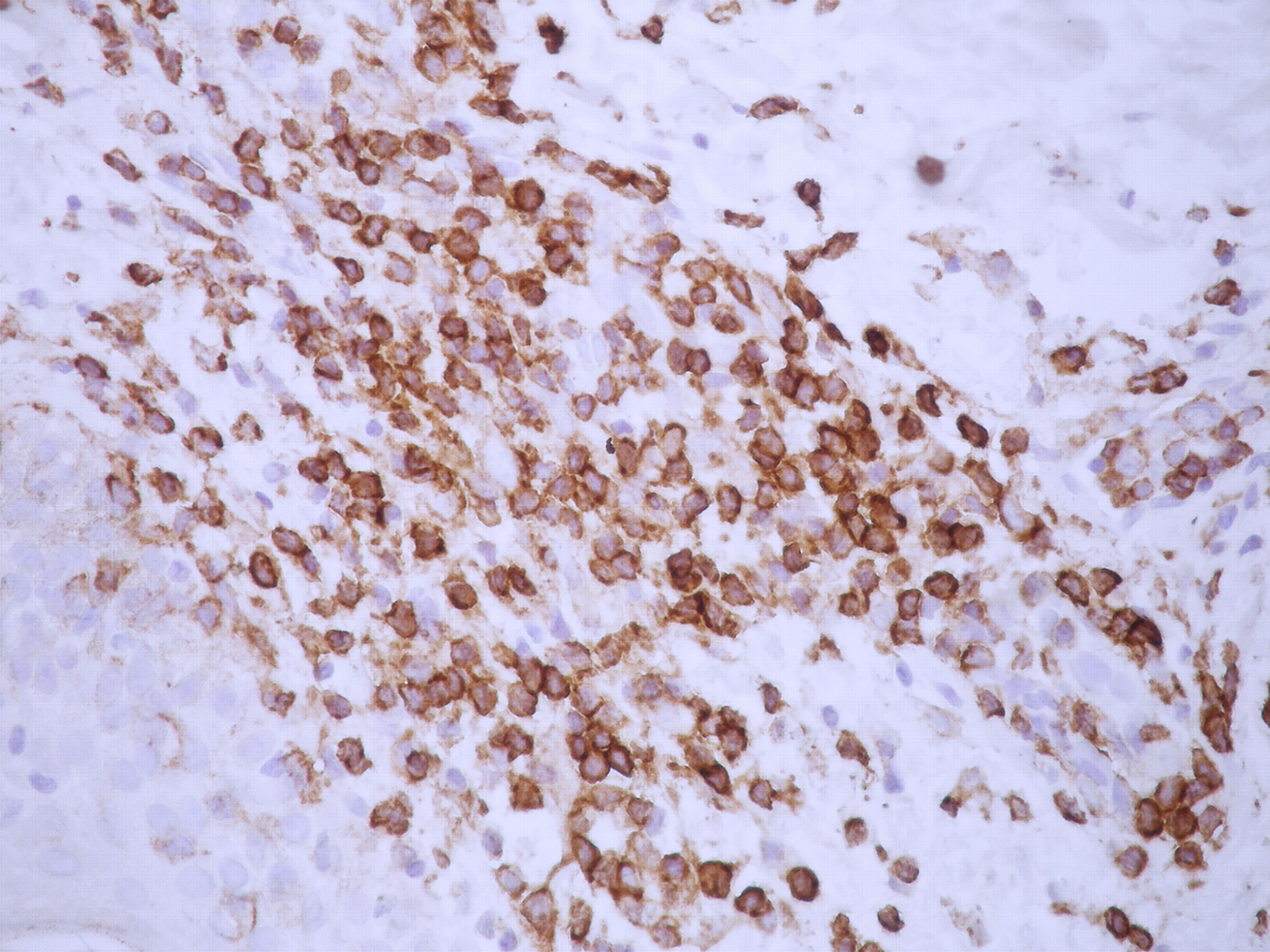

ResultsThe mean score for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD45RO was 3.74±3.88, 5.67±4.40, 2.94±3.42 and 7.68±4.33 in these PR patients (P<0.001). The percentage of positive CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD45RO staining was, respectively, 54.29% (19/35 cases), 69.7% (23/33 cases), 40% (14/35 cases) and 79.41% (27/34 cases) (P<0.05) (Table 1 and Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). However, the staining for CD20 was negative for all skin samples. There was no statistical difference in the mean score of CD3, CD4, CD8 and CD20 staining between the patients with duration of ≤1week and those with duration >1 week. The mean score for CD3 staining in patients with time for remission ≤60 days (4.90±4.21) was higher than that in the patients with time for remission >60 days (2.00±2.5) (P<0.05), whereas there was no statistical difference in the mean score of CD4, CD8 and CD45RO staining (Table 2).

The mean score of CD3, CD4, CD8 and CD45RO staining between groups with remission time ≤60 days and group with remission time >60 days

Previous studies have suggested the association of viral infection and some drugs with the development of PR.3-7 The pathogenesis of PR remains unknown. In 2014, we investigated the levels of IL-2, interferon-γ, IL-4 and IL-10 in the sera of PR patients, and identified a reduced level of interferon-γ. Therefore, we proposed that weakened Th1 response is most likely to contribute to the pathogenesis of PR.2 Hussein et al8 performed immunohistochemical stains for B-cells (CD20), T-cells (CD3), histiocytes (CD68) and T-cells with cytotoxic activity (granzyme-B) in PR and found significantly higher counts of immune cells in lesional skin compared to the normal skin. In the lesional skin, the immune cells were mainly CD3(+) T lymphocytes and CD68(+) cells (histiocytes). Neoh et al9 conducted immunochemical staining on 12 biopsy specimens taken from both herald patches and secondary patches of 6 PR patients. As a result, the dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes stained positively for monoclonal antibodies specific for T-cells, but there was lack of natural killer cell and B-cell activities in all samples. Moreover, the ratio of CD4(+) /CD8 (+) T-cells in the dermal infiltrate was increased in most specimens.

In this study, the results revealed that inflammatory cells with positive CD3, CD4, CD8 and CD45RO staining predominated in the skin lesions of PR patients. The mean score of CD45RO staining was significantly higher than that of CD3, CD4 and CD8 staining (P<0.001). In addition, 27 of 34 (79.41%) patients showed positive CD45RO staining, 19/35 (54.29%) positive CD3 staining, 23/33 (69.7%) positive CD4 staining and 14/35 (40%) positive CD8 staining (P<<0.05). However, all patients were negative for CD20 staining. These findings indicate that T-cells rather than B-cells play an important role in the development of PR. We compared the mean scores of CD3, CD4, CD8 and CD45RO staining between patients with ≤1 week duration and patients with >1 week duration, and between the patients with time for remission ≤60 days and the patients with time for remission >60 days. Patients with time for remission ≤60 days had the higher mean score of CD3 staining than the patients with time for remission >60 days.

ConclusionOur findings support that a predominantly T-cell-mediated immunity participated in the development of PR.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.