Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a rare neoplasm with indolent progression. Since 1981, the Kaposi’s sarcoma epidemic has increased as co-infection with HIV.

Objectives:The study aimed to identify the clinical and demographic characteristics and therapeutic approaches in HIV/AIDS patients in a regional referral hospital.

Methods:We analyzed the medical records of 51 patients with histopathological diagnosis of Kaposi’s sarcoma hospitalized at Hospital Universitário João de Barros Barreto (HUJBB) from 2004 to 2015.

Results:The study sample consisted of individuals 15 to 44 years of age (80.4%), male (80.4%), single (86.3%), and residing in Greater Metropolitan Belém, Pará State, Brazil. The primary skin lesions identified at diagnosis were violaceous macules (45%) and violaceous papules (25%). Visceral involvement was seen in 62.7%, mainly affecting the stomach (75%). The most frequent treatment regimen was 2 NRTI + NNRTI, and 60.8% were referred to chemotherapy.

Study limitations:We assumed that more patients had been admitted to hospital without histopathological confirmation or with pathology reports from other services, so that the current study probably underestimated the number of KS cases.

Conclusion:Although the cutaneous manifestations in most of these patients were non-exuberant skin lesions like macules and papules, many already showed visceral involvement. Meticulous screening of these patients is thus mandatory, even if the skin lesions are subtle and localized.

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is a poorly differentiated mesenchymal neoplasm, first described in 1872 by Moritz Kaposi.1 The disease usually presents with tropism for lymphatics and blood vessels of the skin, but it can occur in other organs. There are four subtypes, with different clinical manifestations: 1) classic (Mediterranean or sporadic); 2) endemic (African); 3) iatrogenic (generally in transplant patients); and 4) epidemic (associated with HIV/AIDS).2,3

The prevalence of epidemic KS, associated with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), increased since the 1980s as a consequence of the spread of HIV infection. It is known as a defining disease for advanced immunodepression. The involvement of human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8) in the etiology of all subtypes of KS was discovered in 1994.4 Today, KS is one of the most common complications of AIDS in industrialized countries. KS occurs in all age groups and mainly in men who have sex with men (MSM).5 In Brazil, there are more than 800,000 persons living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), and KS is the most frequent neoplasm in this group.6 Still, the etiological agent’s prevalence differs in the various populations: 1.1% in previously healthy patients, 20.4-25.9% in patients coinfected with HIV, and 75.3% in patients that are descendants of Indians from the Amazon Region.7-9

In immunocompetent individuals, the disease usually manifests more in the distal parts of limbs, while in immunosuppressed individuals KS behaves like a multifocal systemic disease.10,11 In PLWHA, studies have reported an association with other lymphoproliferative disorders such as Castleman’s disease, and this comorbidity can occur even in the presence of continuous antiretroviral therapy (cART), thus emphasizing the need for early diagnosis.12-14

Continuous ART is essential for avoiding the emergence of KS or rapid progression of the disease in PLWHA with this diagnosis.15 Continuous ART decreased the incidence of KS from approximately 30/1000 cases per patient-year to 0.03/1000 cases per patient-year.3

KS is an aggressive disease that leads to death, usually from other complications like opportunistic infections associated with AIDS.16 In a study of 112 patients with advanced immunodepression, 65 (58.0%) died from opportunistic infections and eight (7.1%) died directly from KS.17-19 This article thus aims to identify the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of persons living with HIV/AIDS and KS, admitted to a tertiary referral hospital in the Amazon Region.

MethodsA retrospective, cross-sectional case series study was performed in persons with a diagnosis of HIV-1 and concurrent histopathological diagnosis of KS from 2004 to 2015. The study group consisted of patients with histopathological confirmation of KS, treated during hospitalization in the Division of Infectious Diseases of Hospital Universitário João de Barros Barreto (HUJBB) during the study period. Inclusion criteria were: adult age (> 18 years), diagnostic confirmation of HIV-1 according to Brazilian Ministry of Health guidelines, and dermatological or endoscopic suspicion of KS with subsequent histopathological confirmation. Exclusion criteria were: patients with incomplete medical charts that prevented meeting the study protocol.

All the clinical, epidemiological, and treatment data and disease history were transcribed from the patient’s charts to the study protocol. Pathology reports were obtained from the database of the Pathology Department of HUJBB, and 113 reports were located with histopathological confirmation of KS. However, some reports referred to the same patient, when more than one biopsy had been performed to investigate KS in different organs. After exclusion of duplicates, there were 69 individuals eligible for the study. Still, 18 patient charts were not located, so 51 individuals and their respective charts were analyzed in relation to the variables age, birthplace, current address, occupation, schooling, skin color, and conjugal status. Clinical variables were classified according to the AIDS Clinical Trial Group (ACTG) guidelines for staging patients. Primary lesions were described as recorded on the medical charts, and we also analyzed the antiretroviral regimen and recorded whether the patients had been referred to chemotherapy.19

The descriptive analysis, inferences, and graphs used BioEstat 5.3, Epi Info 7, and Microsoft Excel 2010.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of HUJBB, in accordance with resolution 466/2012 of the National Health Council/Ministry of Health (CNS/MS) and only began after the license was granted (case review: 787848/2014; CAE: 34639414.7.0000.0017).

One limitation to the study was possible underestimation of KS cases in the study period, since the sample only included patients with histopathological diagnosis performed at the hospital.

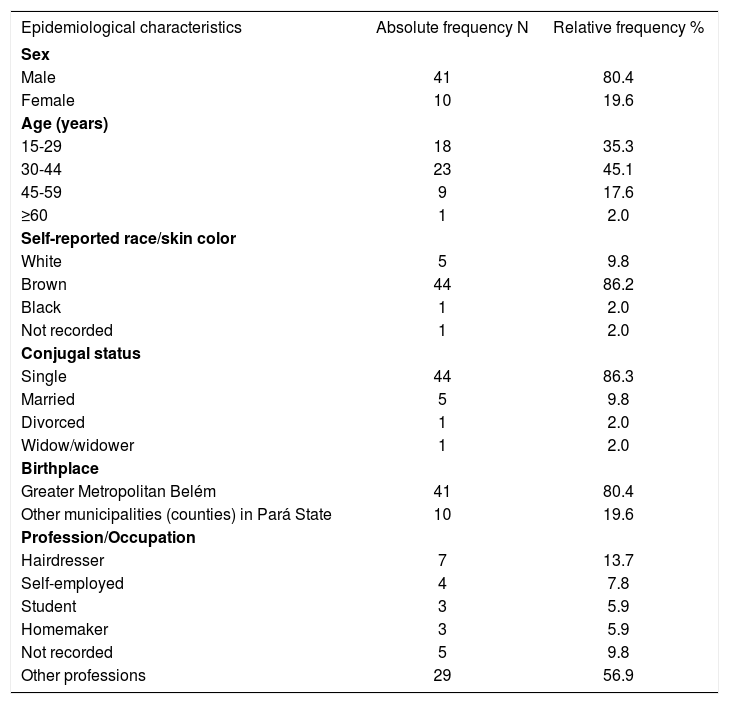

ResultsAs mentioned, of the 51 individuals, the majority were male (80.4%), ranging in age from 20 to 61 years, living in Greater Metropolitan Belém (80.4%), and single (86.3%), with hairdresser as the most frequent occupation (13.7%) (Table 1). As for time since HIV diagnosis, 58.8% had been diagnosed recently, i.e., less than six months previously (Table 2). Of these, 44 were on cART, and the mostly widely used regimen was 2 NNRTI + NRTI (70.5%).

Distribution of persons living with HIV/AIDS and Kaposi’s sarcoma according to gender, age, current address, occupation, and conjugal status, 2004 to 2015, HUJBB, Belém, Pará State, Brazil

| Epidemiological characteristics | Absolute frequency N | Relative frequency % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 41 | 80.4 |

| Female | 10 | 19.6 |

| Age (years) | ||

| 15-29 | 18 | 35.3 |

| 30-44 | 23 | 45.1 |

| 45-59 | 9 | 17.6 |

| ≥60 | 1 | 2.0 |

| Self-reported race/skin color | ||

| White | 5 | 9.8 |

| Brown | 44 | 86.2 |

| Black | 1 | 2.0 |

| Not recorded | 1 | 2.0 |

| Conjugal status | ||

| Single | 44 | 86.3 |

| Married | 5 | 9.8 |

| Divorced | 1 | 2.0 |

| Widow/widower | 1 | 2.0 |

| Birthplace | ||

| Greater Metropolitan Belém | 41 | 80.4 |

| Other municipalities (counties) in Pará State | 10 | 19.6 |

| Profession/Occupation | ||

| Hairdresser | 7 | 13.7 |

| Self-employed | 4 | 7.8 |

| Student | 3 | 5.9 |

| Homemaker | 3 | 5.9 |

| Not recorded | 5 | 9.8 |

| Other professions | 29 | 56.9 |

Source: Research protocol, 2016.

Distribution of persons living with HIV/AIDS and Kaposi’s sarcoma according to time since HIV diagnosis and use of antiretroviral therapy, 2004-2015, HUJBB, Belém, Pará, Brazil

| Treatment characteristics | Absolute frequency N | Relative frequency % |

|---|---|---|

| Time since HIV diagnosis < 6 months | ||

| Yes | 30 | 58.8 |

| No | 16 | 31.4 |

| Not recorded | 5 | 9.8 |

| Total | 51 | 100.0 |

| Use of antiretroviral therapy | ||

| Yes | 44 | 86.3 |

| No | 7 | 13.7 |

| Total | 51 | 100.0 |

| Antiretroviral therapy according to classes | ||

| 2 NRTI* + NNRTI** | 31 | 70.5 |

| 2 NRTI + PI# | 2 | 4.5 |

| 2 NRTI + PI/rμ | 7 | 15.9 |

| Not recorded | 4 | 9.1 |

| Total | 44 | 100.0 |

Source: Research protocol, 2016.

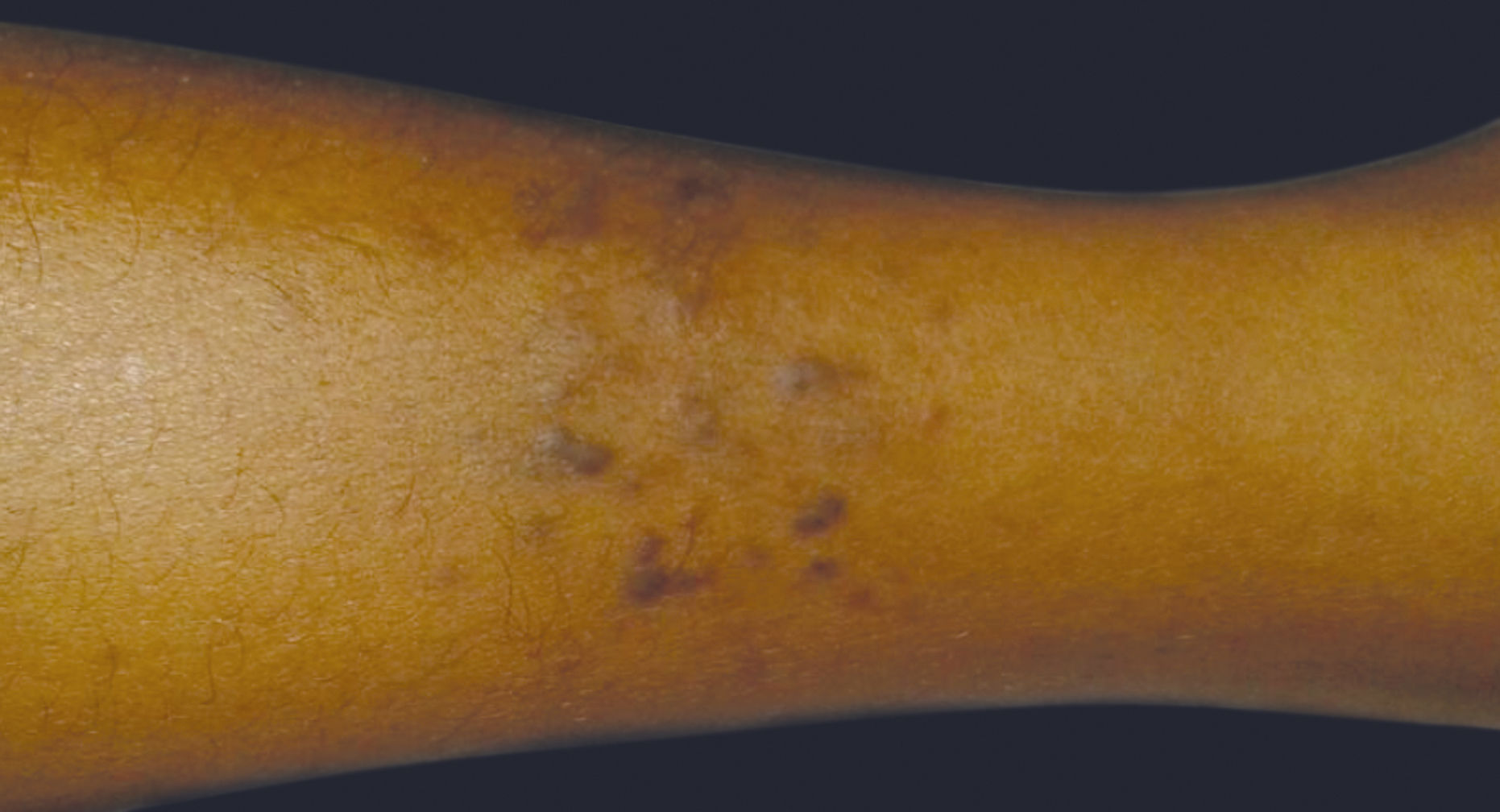

Concerning the clinical characteristics of the disease, the majority presented disseminated skin lesions (39.2%), followed by lesions exclusively on the limbs (15.7%) and on the trunk and limbs (11.8%). The most common primary lesions were violaceous macules (40%) and violaceous papules (22.5%) (Table 3, Figures 1 and 2).

Distribution of persons living with HIV/AIDS and Kaposi’s sarcoma according to location of skin lesions, pattern of primary lesions, and visceral involvement, 2004-2015, HUJBB, Belém, Pará, Brazil

| Clinical characteristics | Absolute frequency | Relative frequency % |

|---|---|---|

| Location of skin lesions | ||

| Face | 1 | 2.0 |

| Face and limbs | 1 | 2.0 |

| Oral cavity | 2 | 3.9 |

| Neck and limbs | 1 | 2.0 |

| Trunk | 1 | 2.0 |

| Limbs | 8 | 15.7 |

| Trunk and limbs | 6 | 11.8 |

| Disseminated | 20 | 39.2 |

| Not recorded | 11 | 21.6 |

| Total | 51 | 100.0 |

| Primary lesion | ||

| Violaceous macules | 16 | 40.0 |

| Violaceous papules | 9 | 22.5 |

| Violaceous nodules | 4 | 10.0 |

| Infiltrated plaques | 4 | 10.0 |

| Violaceous tumor | 2 | 5.0 |

| Ulcerative-vegetative lesion | 5 | 12.5 |

| Total | 40 | 100.0 |

| Visceral involvement | ||

| Yes | 32 | 62.7 |

| No | 5 | 9.8 |

| Not reported | 14 | 27.5 |

| Total | 51 | 100.0 |

| Visceral organs involved | ||

| Stomach | 24 | 75.0 |

| Small intestine | 8 | 25.0 |

| Large intestine | 8 | 25.0 |

| Esophagus | 6 | 18.8 |

| Lung | 3 | 9.4 |

| Chemotherapy performed at the Oncology Service | ||

| Yes | 24 | 47.1 |

| Not referred | 7 | 13.7 |

| Not recorded | 7 | 13.7 |

| Death during hospitalization | 13 | 25.5 |

| Total | 51 | 100.0 |

Source: Research protocol, 2016.

Nearly two-thirds (62.7%) of the individuals presented visceral involvement (n=32/51), and of these, the most frequently affected organ was the stomach (75%; n=24/32). Of all the individuals with KS, 24 (47.1%) had indication of chemotherapy after staging of the neoplastic spread to visceral organs and were accompanied by the hospital’s Oncology Department after discharge. A total of 25.5% of the individuals died in hospital.

DiscussionThe study sample included a majority of adult males, with a mean age of 35 years, similar to studies from the 1990s and corroborating a more recent study in which 88% of the patients were males and with a mean age of 35 years.20-22

Concerning the profession/occupation of KS patients, several studies have shown higher incidence of the disease in individuals with more education, especially health professionals, including dentists, due to the heavy exposure to the saliva of infected patients.22-24 In the current study the most common occupation was hairdresser. Most patients had completed secondary school. One finding that stands out is the high proportion of single patients (86.3%), which raises the question concerning monogamous relationships as a protective factor, as described in the literature, and corroborating various studies on infectious diseases showing that single individuals are much more susceptible to infections from such etiological agents as herpesvirus.25

The large proportion of patients from Greater Metropolitan Belém, the state capital of Pará, is consistent with the literature reporting higher incidence of KS and HIV in the capital cities of underdeveloped countries than in the rural areas. Other regions of Pará also have regional hospitals that can receive patients from their vicinities.26 Interestingly, in urban areas of developed countries where the human development index is similar to that of undeveloped countries, there are also numerous reports of this coinfection, thus highlighting the importance of social determinants and the fact that knowledge of such determinants can help orient public policies for prevention.27

As for time since HIV infection and use of continuous antiretroviral therapy, our results corroborate other studies in the literature. In most of the cases in our study, time since HIV diagnosis was less than a year, so continuous antiretroviral therapy was also recent, which may also have resulted in early diagnosis of KS.28-30 However, this disagrees with the high percentage of visceral involvement in this patient sample. This may mean later HIV diagnosis, often made after the emergence of clinical suspicion of cutaneous KS. Early initiation of continuous antiretroviral therapy in HIV patients is known to decrease the risk of disease progression, especially with viral RNA suppression and subsequent increase in CD4 T-lymphocyte count.31,32 Treatment adherence should also be discussed at length with the patient, since lack of perfect adherence has been shown to be a risk factor (up to 20-fold) that favors dissemination of the disease and systemic manifestations.0105

Other clinical features of KS in this study were similar to those reported in the literature, with skin lesions consisting mainly of violaceous macules and papules, suggesting initial KS lesions but not necessarily the absence of visceral lesions.30,32-34 Importantly, manifestations in other organ systems can precede skin lesions.0115 In visceral involvement, the gastrointestinal tract is the most frequently affected system, especially the stomach.9,30,35

ConclusionAlthough the involvement of the skin manifested in most of the cases was non-exuberant, with initial lesions like macules and papules, many of the patients had already presented visceral involvement, emphasizing the need for careful screening of patients even when skin lesions are subtle or localized. This study addressed the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of individuals with Kaposi’s sarcoma and HIV in an Amazonian population.

Financial support: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES.

Conflict of interest: None.