Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds is a chronic relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by sterile pustules compromising skin folds, scalp, face and periorificial regions. It predominantly affects women. Demodicosis is an inflammatory disease associated with cutaneous overpopulation of the mite Demodex spp., the pathogenesis of which is not completely established, but is frequently related to local immunodeficiency. A case of a young woman with amicrobial pustulosis of the folds, and isolated worsening of facial lesions, is reported; investigation revealed overlapping demodicosis. There was complete regression of lesions with acaricide and cyclin treatment. This case warns of a poorly diagnosed but disfiguring and stigmatizing disease, often associated with underlying dermatoses or inadvertent treatments on the face.

Amicrobial pustulosis of the folds (APF) is a chronic, relapsing neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by sterile pustules involving the cutaneous folds, the genital region and the scalp.1,2

Ninety percent of those affected are women, and the average age at diagnosis is 30 years. Clinically, the disease is characterized by the sudden appearance of follicular and nonfollicular pustules on the large folds, as well as on small folds such as the region adjacent to the nostril, the retroauricular region, and the external auditory canal. The pustules may coalesce, forming ulcerative and exudative erythematous plaques and even abscesses.1,2

APF can be associated with various autoimmune diseases—including erythematous lupus, mixed connective tissue disease, myasthenia gravis, Sjögren’s syndrome, celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura—or with the presence of circulating autoantibodies. APF has also been reported as an adverse effect of immunobiological medications (anti-TNF).1–5

Therapy is based on case reports, with emphasis on systemic corticosteroids.1

Demodicosis (DMD) is an inflammatory disease associated with cutaneous overpopulation of the mite Demodex spp., a saprophyte of human cutaneous microbiota. The presence of the mite on the cutaneous surface varies from 12% to 72%, increasing with age up to 100% among elderly people.6

The pathogenesis is not yet well established, but it is believed that a local immunodeficiency favors the proliferation of the mites.7

We report a case of a young female patient with APF who presented evident and isolated worsening of facial lesions, an investigation of which revealed overlapping DMD and not an exacerbation of the underlying disease.

Case ReportThe 32-year-old female patient presented a history of sporadic dermatological treatment over six years for chronic lesions affecting the face, scalp, ears and axillae. She had been treated with antiseptic soaps, tetracyclines, benzathine penicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate and topical metronidazole, with diagnostic hypotheses of rosacea and hidradenitis suppurativa; however, the response was unsatisfactory. Examination found ulcerative, exudative and crusted plaques on the scalp and in the pubic and inguinocrural regions; erythema and centrofacial infiltration; papules and pustules distributed over the face; erythema, exudation and crusts on the nostrils and on the external acoustic meatus; and axillary pustules and nodules (Figure 1). The hypothesis of APF was suggested, and autoimmunity screening showed antinuclear factor (ANF) at 1/320 with an agglomerated nucleolar pattern, anti-smooth muscle antibody at 1/80, and low complement C4.

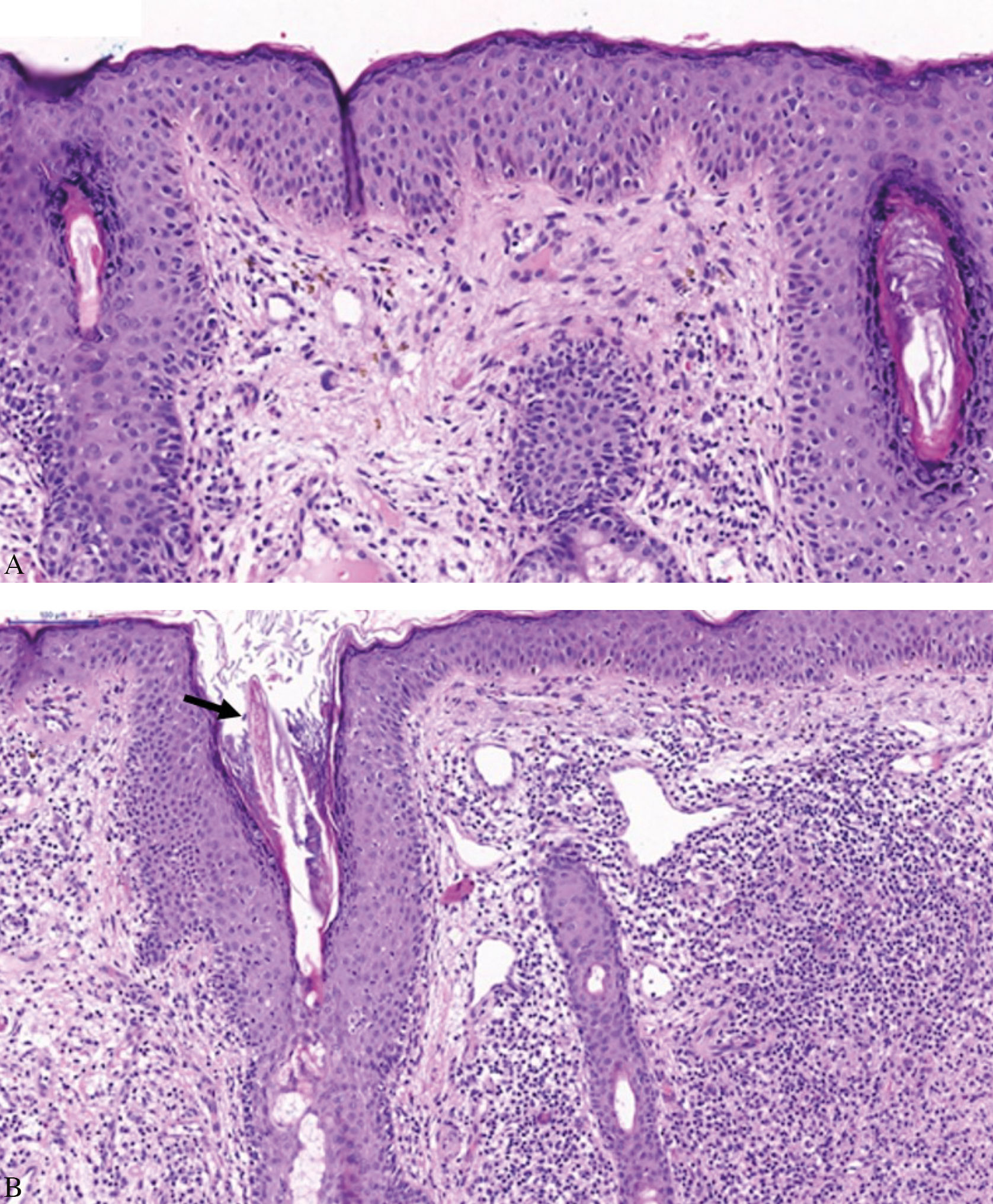

Prednisone (1 mg/kg/day) and zinc sulfate (100 mg/day) were administered, with lesions regressing almost completely in three weeks, but reactivating after reduction of the corticosteroid dosage. Methotrexate (10 mg/week) was incorporated, allowing maintenance of the prednisone at 10 mg/day. After nine months of this therapy, the facial lesions worsened, with papules and infiltrated erythematoviolaceous plaques in the centrofacial and malar regions, and numerous pustules; however, improvement continued in other areas normally compromised by APF (Figure 2). A biopsy of the facial lesion was performed, demonstrating hyperkeratosis, follicular plugs, and dilation of the infundibula with a large number of Demodex folliculorum, associated with lymphohistiocytic folliculitis with granulomatous focus (Figure 3).

Subsequently, ivermectin (12mg/week) and doxycycline (100mg/day) were used, with the lesions regressing after four weeks of treatment (Figure 2). After thirteen months of follow-up, the condition was stable, without recurrence of the facial lesions.

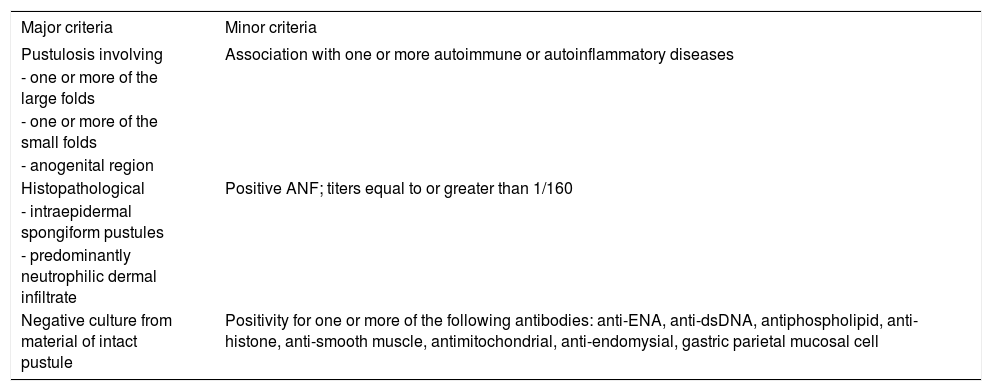

DiscussionAPF is an uncommon entity, with approximately 30 cases described in the literature. In a series of cases, Marzano et al. (2008)2 suggested diagnostic criteria for the disease, based on the presence of three major criteria and at least one minor criterion (Chart 1). The immunological changes identified in the present case were the ANF of 1/320 and the anti-smooth muscle antibody of 1/80.

Diagnostic criteria for amicrobial pustulosis of the folds

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Pustulosis involving | Association with one or more autoimmune or autoinflammatory diseases |

| - one or more of the large folds | |

| - one or more of the small folds | |

| - anogenital region | |

| Histopathological | Positive ANF; titers equal to or greater than 1/160 |

| - intraepidermal spongiform pustules | |

| - predominantly neutrophilic dermal infiltrate | |

| Negative culture from material of intact pustule | Positivity for one or more of the following antibodies: anti-ENA, anti-dsDNA, antiphospholipid, anti-histone, anti-smooth muscle, antimitochondrial, anti-endomysial, gastric parietal mucosal cell |

Sour Marzano et al., 2008.2

The cause of the disease is unknown, though complement activation by immunocomplexes and the consequent chemotaxis of neutrophils are believed to participate, with formation of subcorneal pustules. However, the immunofluorescence of tissue samples from those with APF is negative, with no immunocomplex deposits being identified.1–3,8

Systemic corticosteroids are the most utilized treatment. There are occasional reports of improvement with colchicine, hydroxychloroquine, cyclosporine, cimetidine, anakinra, vitamin C and supplementation with zinc.1

DMD involves clinically evident infestation by the mite Demodex spp. Some authors suggest that it be classified into primary and secondary forms; the secondary form would occur in the context of local or systemic immunosuppression. Inflammatory facial dermatoses, such as APF, are considered as local immunosuppression.9

Some authors suggest that the higher the density of mites, the greater the infundibular inflammation and, therefore, the higher the probability of a clinical lesion due to infestation. Manifestations can occur due to a large number of mites in the follicle as well as to their presence in the dermis. Furthermore, antigenic proteins from Bacillus oleronius, carried by Demodex spp., may be the antigenic stimulus of the inflammatory response, which is expressed clinically as inflammatory pustules.9,10

The treatments most described for DMD are retinoids, permethrin and topical metronidazole, in addition to ivermectin and oral metronidazole. The action of antimicrobials such as metronidazole—as well as cyclines and macrolides, which show therapeutic efficacy in some cases—may be explained both by their anti-inflammatory effect and by their action on Bacillus oleronius.10

This case warns of a rarely diagnosed dermatosis that can mimic the exacerbation of other underlying inflammatory facial dermatoses, particularly during the use of immunosuppressants. Proper diagnosis and prompt treatment, with a focus on acaricidal medications, enables the resolution of this generally disfiguring and stigmatizing exacerbation.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interests: None.