Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a rare benign panniculitis found in term and post-term neonates. Diagnosis is based on clinical characteristics and specific alterations in the adipocytes, detected by anatomical pathology. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn can occur in uncomplicated pregnancy and childbirth. However, perinatal complications such as asphyxia, hypothermia, seizures, preeclampsia, meconium aspiration, and even whole-body cooling used in newborns with perinatal hypoxia/anoxia may be associated with this entity.

We report a 10-day-old patient born at term by c-sectiondue to fetal bradycardia resulting from severe perinatal asphyxia (one and five-minute Apgar score 2 and 6, respectively), and who underwent whole-body cooling. After discharge from the neonatal ICU, at 9 days of age, the infant began to present multiple soft and non-adherent purple-erythematous nodules on the dorsum, in addition to a single similar lesion located on the left shoulder (Figure 1). Laboratory findings revealed thrombocytopenia and hypoglycemia.

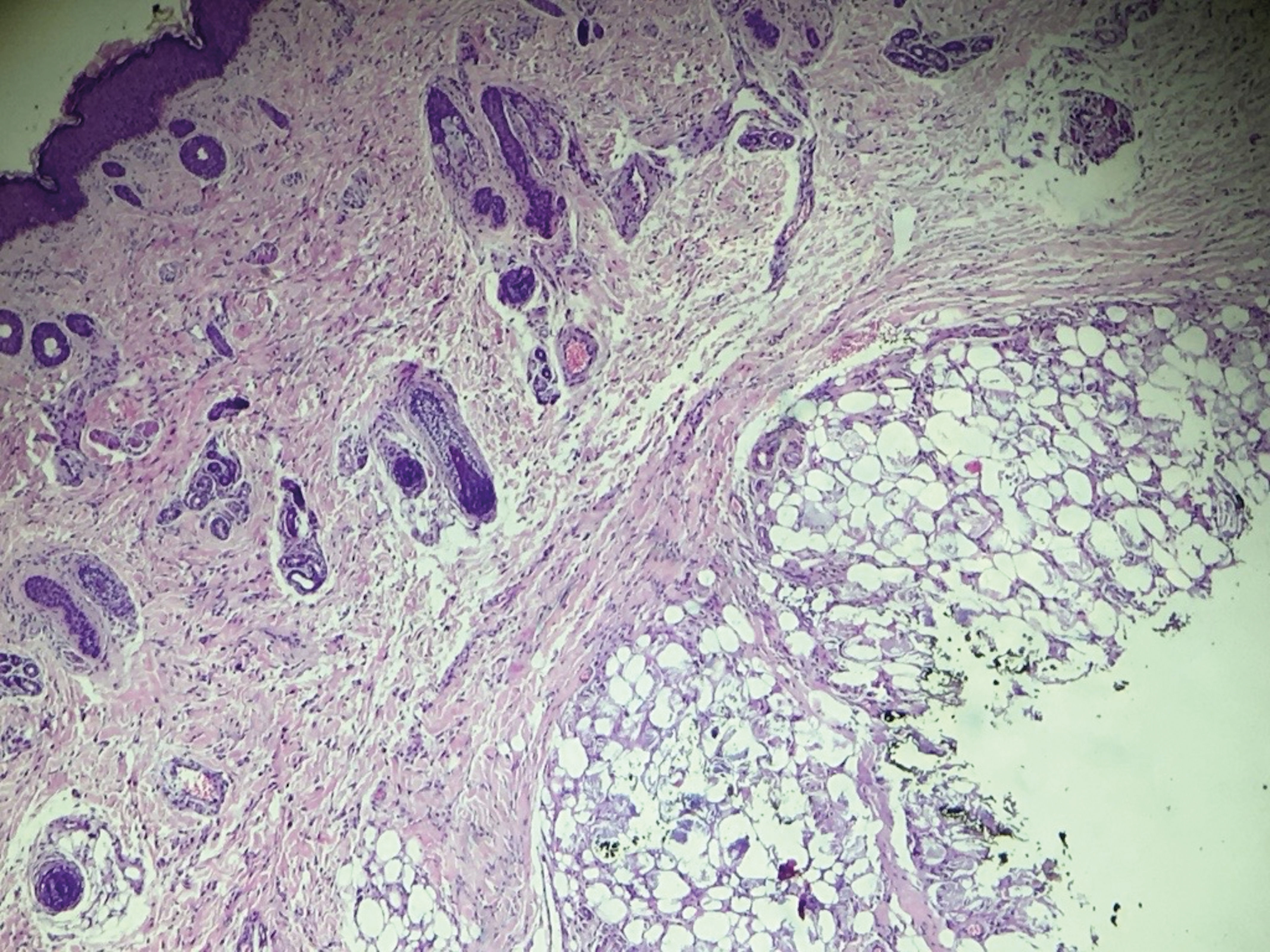

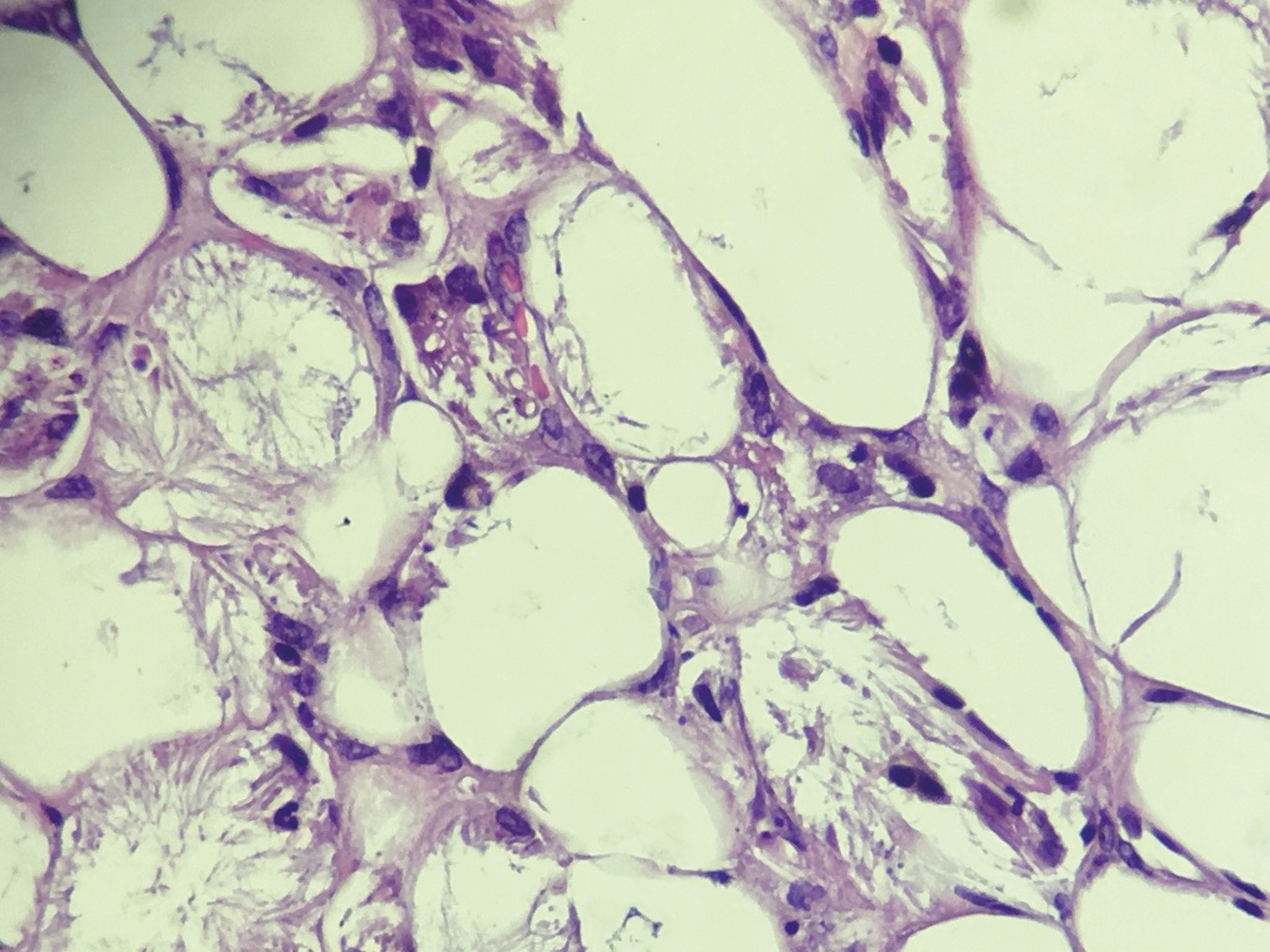

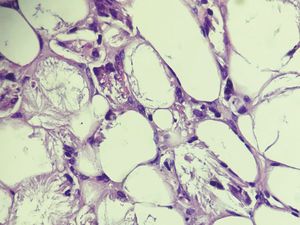

Ultrasound of the skin and soft tissues was initially performed, showing an increase in echogenicity of subcutaneous tissue with hypoechoic and heteroechoic areas, unamenable to puncturing, with no alterations in the underlying muscular planes. Subsequent workup included a biopsy of the left subscapular nodule, which showed preservation of the epidermis and dermis and lobular panniculitis. The adipose lobules of the hypodermis showed histiocytic reaction and extensive necrosis, characterized by intracytoplasmic deposits in the adipocytes that formed radial, needle-shaped crystals, representing the triglyceride crystals dissolved during the histological processing of the sample (Figures 2 and 3).

Clinical-histopathological correlation confirmed the diagnosis of subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn (SFNN).

SFNN is a rare panniculitis that occurs in the neonatal period. Although it can be self-limited, it may evolve with relevant systemic alterations, especially acute renal injury secondary to hypercalcemia. It usually affects term newborns that have undergone birth trauma, or complicated by dystocia, asphyxia, or meconium aspiration.1

The etiology of SFNN is unknown, but maternal factors (Rh incompatibility, preeclampsia, cocaine use, and calcium channel blockers) and fetal factors (whole-body cooling, perinatal asphyxia, and sepsis) appear to be involved.2 It is postulated that neonatal asphyxia leads to shunting of blood from the skin and fat tissue to nobler structures like the heart and brain, leading in turn to fat necrosis.3 Thrombocytopenia usually occurs simultaneously with the lesions and can result from platelets being sequestered by the nodules. Hypercalcemia is found in 25% of the cases and may be present before the subcutaneous nodules appear. The regression of the lesions is usually associated with an increase in serum calcium levels, especially due to the increase in the release of prostaglandins, release of calcium from the necrotic tissue, and the greater release of 1,25-di-hydroxyvitamin D3 by the granulomata.2,4 This alteration is highly important, since failure to implement prompt therapy can lead to severe complications such as nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and acute renal injury.5

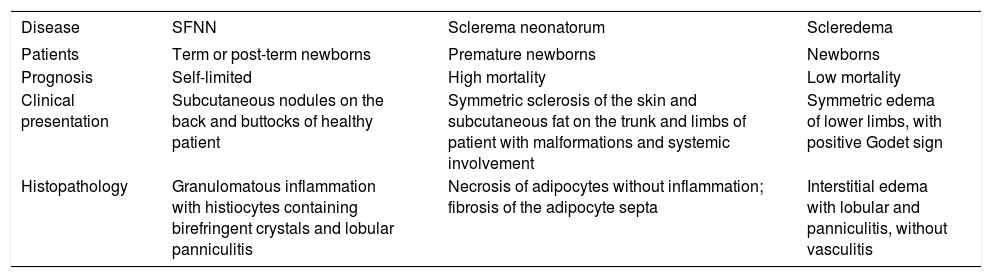

Diagnosis is made by correlating clinical and histopathological features. Biopsy specimens classically present a granulomatous inflammatory reaction, lobular panniculitis, and multinucleated giant cells with birefringent crystals under polarized light, which represent foci of calcification. Lesions biopsied soon after the onset of the condition can present a predominantly neutrophilic pattern with fat necrosis associated with few multinucleated cells, with discharge of sterile pus from the biopsy site.6,7 The most important differential diagnosis is sclerema neonatorum, a disorder in which there is thickening of the skin secondary to fibrosis of the trabecular septa of the adipocytes’ involvement of the muscle and bone tissue, associated with congenital malformations, cyanosis, respiratory disorders, and sepsis.8 Another differential diagnosis is scleredema, which presents progressive edema of the extremities and stiffening of the affected limbs, usually preceded by gastrointestinal or respiratory infections; anatomical pathology reveals intense interstitial edema associated with lobular panniculitis without vasculitis.9Chart 1 compares the clinical forms and histopathological findings of the three diseases.

Clinical and histopathological findings of SFNN and its differential diagnoses

| Disease | SFNN | Sclerema neonatorum | Scleredema |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Term or post-term newborns | Premature newborns | Newborns |

| Prognosis | Self-limited | High mortality | Low mortality |

| Clinical presentation | Subcutaneous nodules on the back and buttocks of healthy patient | Symmetric sclerosis of the skin and subcutaneous fat on the trunk and limbs of patient with malformations and systemic involvement | Symmetric edema of lower limbs, with positive Godet sign |

| Histopathology | Granulomatous inflammation with histiocytes containing birefringent crystals and lobular panniculitis | Necrosis of adipocytes without inflammation; fibrosis of the adipocyte septa | Interstitial edema with lobular and panniculitis, without vasculitis |

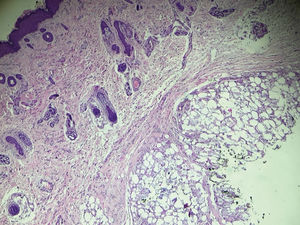

Management of patients with SFNN involves constant clinical follow-up for at least six months and laboratory surveillance of potential complicationslike hypoglycemia, hypercalcemia, and thrombocytopenia.9 It is thus important to orient parents on the signs and symptoms of hypercalcemia in order to initiate prompt treatment. In the current case the patient remained in regular follow-up and evolved without complications (Figure 4). In general, since SFNN is a benign, self-limited condition, complete resolution of the lesions can be expected, without scarring.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.