Dear Editor,

Currently, cutaneous adverse drug reactions are a growing problem in which diagnosis can be challenging due to the existence of multiple drugs, diverse pharmacological interactions and symptoms that mimic a large variety of skin diseases. We report a case of a 23-year-old female patient that presented a 3-year history of dysuria, vulvar bleeding and painful oral ulcerations that healed spontaneously in approximately 10 days (Figure 1). The episodes were sporadic, but the symptoms became more exuberant with every relapse, leading to conjunctival hyperemia and eyelid edema. Systemic lupus erythematosus and Behçet’s disease were considered. Laboratory tests, including viral serologies, ANF, ESR and ANCA showed normal results and pathergy test was negative.

Although a definite diagnosis was not reached, the patient was started on prednisone 0.5mg/kg/day and azathioprine 150mg/day with partial clinical control. Even though the patient was on immunosuppressant drugs, erythematous macules appeared on the lower limbs, which regressed within a few hours. However, in every recurrence, the lesions extended to the trunk and became more numerous, pruritic, erythematous and violaceous, leaving residual pigmentation (Figure 2). At this moment, we hypothesized fixed drug eruption with cutaneous and mucous involvement. The patient reported occasional use of nimesulide to treat a possible viral infection of the upper respiratory tract.

Skin biopsy revealed hypergranulosis, necrosis of keratinocytes, acrosyringium adjacent to the luminal region, and infundibular keratinocytes immediately adjacent to the follicular ducts. It also revealed a mild lymphocytic infiltrate, with few eosinophils and numerous melanophages located around superficial vessels of the papillary dermis, compatible with the hypothesis of drug eruption.

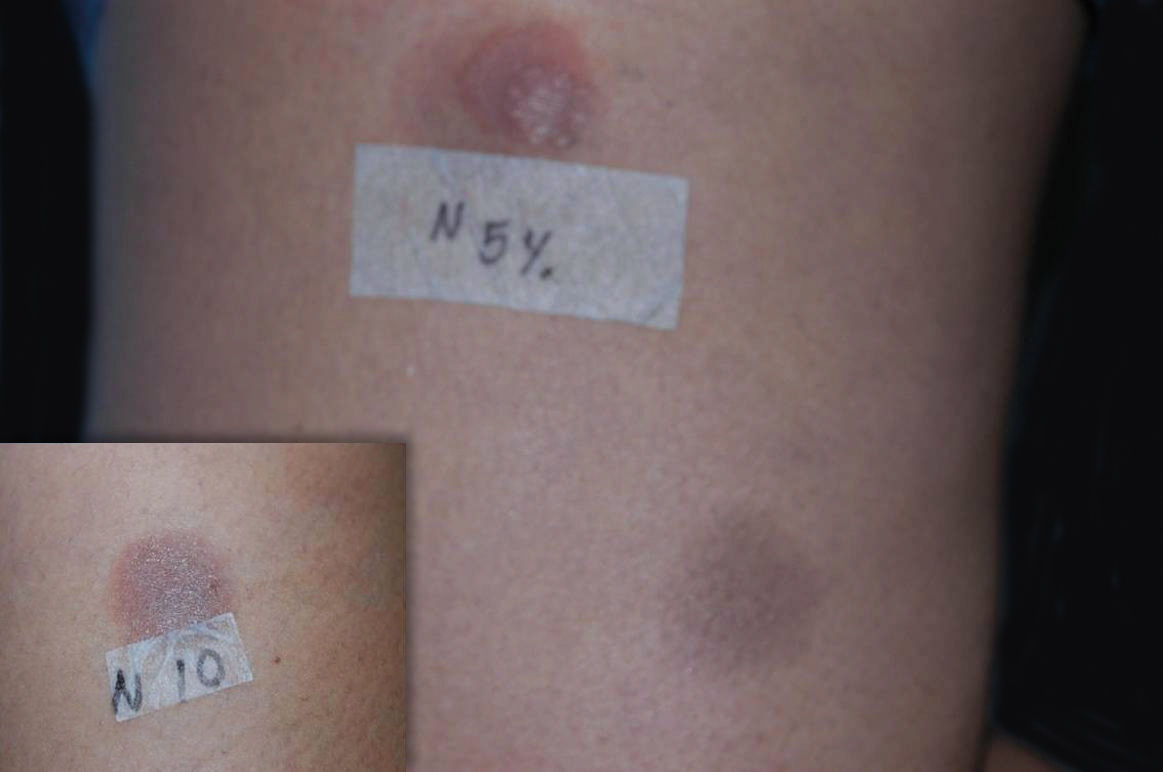

Once the anti-inflammatory was withdrawn, the patient showed significant clinical improvement, which allowed the corticosteroid and azathioprine to be discontinued. In order to confirm the diagnosis, the patient was submitted to patch tests with Brazilian’s standard and cosmetic battery, as well as 1%, 5% and 10% nimesulide in vaseline. Since nimesulide is not available for patch tests in Brazil, the drug was manipulated to fit the criteria described above. Both the drug concentrations and the vehicle used were obtained from the literature.1 The drug was applied on the skin of both the patient’s back and on residual lesions on the lower limbs. Among the standard substances used, patch tests were positive for cobalt chloride (+++) and nickel sulfate (++); among the nimesulide concentrations used, patch tests were positive only for those applied on residual lesions at both 5% and 10% (Figure 3).

The diagnosis of fixed drug eruption relies on a thorough medical history as it allows the correlation between clinical symptoms and drug use. The anatomopathological exam is not specific. Although reexposure tests are considered gold-standard for diagnosis, the harmful effects caused can be avoided by performing patch tests.1-3 Patch test efficiency can be variable, however it does yield good results for cases induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).1,2

Given that the pathophysiology of fixed drug eruption is most likely related to the persistence of memory T cells on affected regions of the skin, patch tests can be improved by applying the suspected drug on residual lesions.1,2 False negative tests are most likely caused by a reduced drug absorption through stratum corneum or the inability of of the original form of the drug to activate the immune system, which would be accomplished only by systemic metabolization into immunologically active metabolites.1

The most common cutaneous side effects of nimesulide are itching and exanthema. However, few case reports of fixed drug eruption associated to nimesulide have been published, and even less showing mucous involvement.4,5 The most effective intervention is discontinuing the drug. Nimesulide may present crossed-reactions to sulfonamides and to other COX-2 enzyme inhibitors, and thus their use should be avoided or preceeded by therapeutic testing.4

We report the diagnostic challenges related to the exuberant initial presentation of mucous membranes only. It is also worth mentioning that the symptoms did not improve with the use of immunosuppressant drugs while the intermitent exposure to the NSAID continued. Additionally, we point out that the patch test results were positive only on residual lesions and on the higher concentrations of the drug, indicating the most adequate concentrations and testing areas for the patch test with this medication.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interests: None.