Background: Psoriasis has a significant impact on quality of life (QoL). Sexual life can also be affected, with sexual dysfunction being reported by 25-70% of patients.

Objectives: To determine the occurrence of sexual dysfunction and evaluate QoL in women with psoriasis.

Methods: This case-control study included women aged 18-69 years. The validated Brazilian Portuguese versions of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) were administered to all participants to assess sexual function and QoL, respectively. Patients with psoriasis underwent clinical evaluation for the presence of comorbidities, especially psoriatic arthritis and other rheumatic manifestations. Location of lesions and the extent of skin involvement were also assessed.

Results: The sample consisted of 150 women, 75 with diagnosis of psoriasis and 75 healthy controls. Prevalence of sexual dysfunction was high in women with psoriasis (58.6% of the sample). Prevalence was statistically higher in women with psoriasis than in controls (P = 0.014). The SF-36 domain scores were also lower in women with psoriasis, with role limitations due to physical health, limitations due to emotional problems, and mental health being the most affected domains.

Study limitations: Sample size was calculated to evaluate the association between the occurrence of sexual dysfunction and psoriasis, but it did not include the determination of the possible causes of this dysfunction.

Conclusions: QoL and sexual function were altered in women with psoriasis and should be taken into consideration when assessing disease severity.

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that involves mainly the skin and joints, affecting 1-3% of the world population.1-3 In Brazil, there are still no studies on its incidence and prevalence, but it is estimated that 1% of the Brazilian population has psoriasis.4 Its impact on quality of life (QoL) has been studied since the 1970s, when Jobling observed that more than 80% of patients presented difficulties in establishing social relations, considered the most daunting aspect of their illness.5,6 Since then, interest has increased in the quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing of psoriasis patients. Many studies have shown that psoriasis triggers feelings of depression, shame, and anxiety, culminating in social isolation.7-11 Al-Mazeedi et al. reported that psoriasis inhibited new relations in 48.2% of patients, and two-thirds were concerned about the reactions and perceptions of others in relation to their condition.8

One of the key points in maintaining QoL, as defined by the World Health Organization, is sexuality.12 Sexual dysfunction is characterized by lack of adequate functioning of one of the phases comprising the sexual cycle. In women, sexual dysfunction is defined as disorders of desire, libido, or arousal, pain or discomfort, and anorgasmia.13

Although sexual dysfunction is a common complaint, affecting 30 to 70% of psoriasis patients, few studies have analyzed the impact of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis on quality of sexual life, and none has addressed the Brazilian population.14,15 The aim of this article was to assess the occurrence of sexual dysfunction in psoriasis using a case-control study with Brazilian women.

MethodsA case-control study was performed with a convenience sample consisting of patients with a diagnosis of psoriasis (psoriasis group) treated at a specialized Dermatology Outpatient Service at Hospital Universitârio de Brasília (HUB) and healthy volunteers (healthy control group), matched for age, recruited at the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic of Hospital das Forças Armadas (HFA) from July 2011 to October 2012. The control group consisted of women that were accompanying patients at the outpatient clinic and patients returning for follow-up, previously treated and without clinical complaints at the time of recruitment.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Brasília (case review 010/2011).

Inclusion criteria for all the women were: age 18 to 69 years, active sexual life, and clinical diagnosis of psoriasis, as determined by the same physician, an experienced dermatologist, and or clinical-pathology study. For the control group, an inclusion criterion was the absence of diagnosis of psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.

Exclusion criteria were: gynecological disorder potentially affecting sexual function (including vaginitis, endometriosis, chronic pelvic pain, malignant neoplasm, uterine cervical dystopia, vaginism, and alterations of the pelvic anatomy); pregnancy; prior psychiatric diagnosis or concurrent with psoriasis (depression, anxiety, phobias, psychopathy); diagnosis of rheumatic diseases or others that course with arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, microcrystalline arthritis), which can cause confounding or doubt as to the diagnosis of possible psoriatic arthritis; diagnosis of chronic, extensive skin disorders such as dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, bullous dermatoses, vitiligo, ichthyosis, acne grade two or greater, and genital mucocutaneous diseases.

After signing informed consent, all participants underwent a clinical assessment that recorded epidemiological data like age, ethnicity, schooling, and marital status, besides clinical data such as past medical history and use of medications. In psoriasis patients, the location of the lesions was also verified (genital involvement, ungual involvement, and involvement of exposed skin areas, the latter defined for purposes of this study as lesions located on the face, scalp, and hands) and extent of the disease, assessed by the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI).16 Next, patients were submitted to the version validated in Brazilian Portuguese of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and the Medical Outcome Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).17,18 Finally, women with any complaints pertaining to the joints were examined by an experienced rheumatologist (always the same physician), in order to assess the presence of psoriatic arthritis, based on the CASPAR classification criteria.19

The FSFI is a questionnaire that aims to assess female sexual response through analysis of the five domains of sexual function: desire and subjective arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain/discomfort. Individual scores are obtained by the sum of the items that include each domain (simple score), which are multiplied by this domain’s factor, furnishing the weighted score. The final score (minimum two, maximum 36) is obtained by the sum of the weighted scores in each domain. A total score of 26 or less indicates greater risk of sexual dysfunction.20

SF-36 is a 36-item questionnaire that assesses eight domains of QoL: physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, and mental health. The score for each domain varies from zero to 100, where zero is the worst health status and 100 is the best.18

Statistical analysisThe sample calculation was done initially in a pilot study with 67 women (47 with psoriasis and 20 controls), evaluating the variables obtained with the desire indices from the FSFI by means of the Wilcoxon text with 95% confidence interval, leading to 88% test power for a sample of 150 women with a difference of one point.

Analyses of the association between variables used the R software, version 2.15.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, URL http://www.R-project.org/). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality was used to verify whether the sample’s data showed normal distribution. The distribution was considered normal if p>0.05. Analysis of categorical variables was based on the chi-square test of independence. When data for the variables were less than five, the p-value from the Monte Carlo simulated Fisher’s exact test was used, as proposed by Hope, 1968.21 The association between quantitative variables was investigated in two ways: a) by means of categorization of the variables, followed by analysis using the chi-square test or Monte Carlo simulated p-value; b) by calculation of Pearson’s correlation coefficient, when the variables showed two-tailed normal distribution, or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient for cases that did not show this distribution. Finally, analysis of covariance was applied to assess quantitative target variables from FSFI and SF-36, adjusted for covariables that could influence the study’s results. The categories of some covariables were grouped so as to increase the model’s explanatory capacity and goodness of fit. Statistical significance was set at 5%.

RESULTSThe study’s sample size was 150 women, of whom 75 in the control group and 75 in the psoriasis group, both with mean age 45 years and standard deviation approximately 12 years. All the patients diagnosed with psoriasis were caucasian or of mixed races. The control group included a few black and Asian-descendent women, but the vast majority were caucasian or of mixed races (92%). In both groups, the majority of women were married, but the proportion of unmarried women and those not living with a partner (i.e., single, divorced, or widows) was higher (42.66%) in the psoriasis group. As for education, the control group included predominantly women with more than seven years of schooling, while the psoriasis group included mostly those with one to seven years of schooling. Only two illiterate women participated in the study, both with psoriasis.

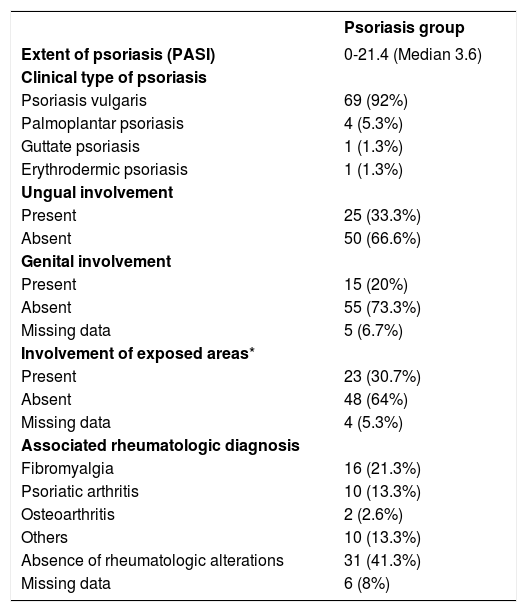

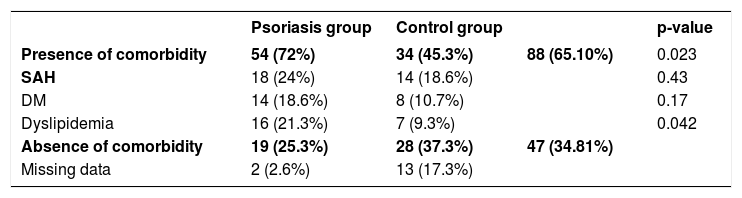

As for clinical status of psoriasis, most of the patients presented psoriasis vulgaris, and for disease site, 20% presented genital involvement, 33% ungual involvement, and 30% with lesions on exposed areas. PASI scores varied from 0 to 21.4, with a median score of 3.6 (interquartile range, 6.3). Comorbidities were present in 45% of the control group and 72% of the psoriasis group. Chi-square test showed a statistically significant association between presence of comorbidities and psoriasis (p=0.023). Rheumatological assessment was performed in 38 of the 75 patients diagnosed with psoriasis, of whom 16 had a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, ten of psoriatic arthritis, and two of osteoarthritis; 31 patients denied any kind of rheumatic manifestation. Tables 1 and 2, respectively, show the psoriasis group’s clinical characteristics and analysis of comorbidities.

Clinical characteristics of psoriasis group

| Psoriasis group | |

|---|---|

| Extent of psoriasis (PASI) | 0-21.4 (Median 3.6) |

| Clinical type of psoriasis | |

| Psoriasis vulgaris | 69 (92%) |

| Palmoplantar psoriasis | 4 (5.3%) |

| Guttate psoriasis | 1 (1.3%) |

| Erythrodermic psoriasis | 1 (1.3%) |

| Ungual involvement | |

| Present | 25 (33.3%) |

| Absent | 50 (66.6%) |

| Genital involvement | |

| Present | 15 (20%) |

| Absent | 55 (73.3%) |

| Missing data | 5 (6.7%) |

| Involvement of exposed areas* | |

| Present | 23 (30.7%) |

| Absent | 48 (64%) |

| Missing data | 4 (5.3%) |

| Associated rheumatologic diagnosis | |

| Fibromyalgia | 16 (21.3%) |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 10 (13.3%) |

| Osteoarthritis | 2 (2.6%) |

| Others | 10 (13.3%) |

| Absence of rheumatologic alterations | 31 (41.3%) |

| Missing data | 6 (8%) |

Assessment of comorbidities in the psoriasis group and control group (chi-square test)

| Psoriasis group | Control group | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of comorbidity | 54 (72%) | 34 (45.3%) | 88 (65.10%) | 0.023 |

| SAH | 18 (24%) | 14 (18.6%) | 0.43 | |

| DM | 14 (18.6%) | 8 (10.7%) | 0.17 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 16 (21.3%) | 7 (9.3%) | 0.042 | |

| Absence of comorbidity | 19 (25.3%) | 28 (37.3%) | 47 (34.81%) | |

| Missing data | 2 (2.6%) | 13 (17.3%) |

SAH - systemic arterial hypertension; DM - diabetes mellitus

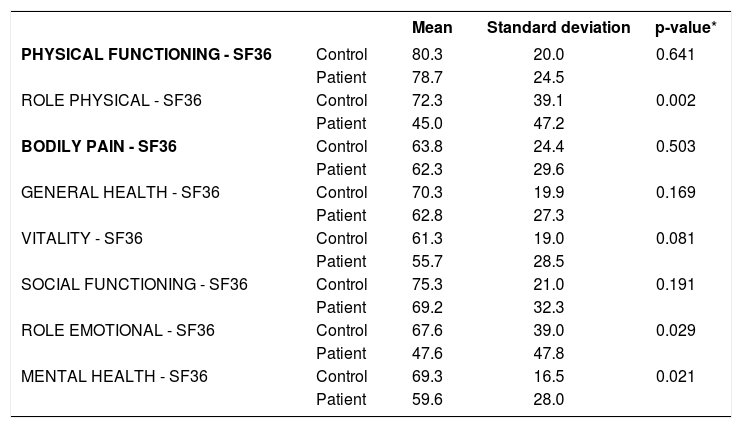

Analysis of covariance revealed significantly worse indices in the psoriasis group, adjusted for age, skin color, schooling, and marital status in the domains role physical (p=0.002), role emotional (p=0.029), and mental health (p=0.021) (Table 3).

Comparison of quality of life (SF-36) between the groups with and without psoriasis, adjusted by age, ethnicity, schooling, and marital status (analysis of covariance)

| Mean | Standard deviation | p-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHYSICAL FUNCTIONING - SF36 | Control | 80.3 | 20.0 | 0.641 |

| Patient | 78.7 | 24.5 | ||

| ROLE PHYSICAL - SF36 | Control | 72.3 | 39.1 | 0.002 |

| Patient | 45.0 | 47.2 | ||

| BODILY PAIN - SF36 | Control | 63.8 | 24.4 | 0.503 |

| Patient | 62.3 | 29.6 | ||

| GENERAL HEALTH - SF36 | Control | 70.3 | 19.9 | 0.169 |

| Patient | 62.8 | 27.3 | ||

| VITALITY - SF36 | Control | 61.3 | 19.0 | 0.081 |

| Patient | 55.7 | 28.5 | ||

| SOCIAL FUNCTIONING - SF36 | Control | 75.3 | 21.0 | 0.191 |

| Patient | 69.2 | 32.3 | ||

| ROLE EMOTIONAL - SF36 | Control | 67.6 | 39.0 | 0.029 |

| Patient | 47.6 | 47.8 | ||

| MENTAL HEALTH - SF36 | Control | 69.3 | 16.5 | 0.021 |

| Patient | 59.6 | 28.0 |

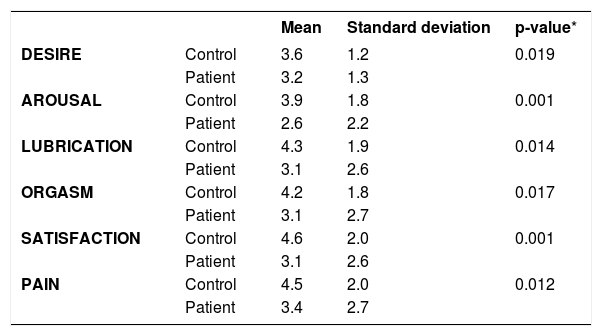

Forty-four patients (58.6%) and 29 controls (38.6%) showed FSFI score less than or equal to 26, with a chi-square test with p-value 0.014, demonstrating higher occurrence of sexual dysfunction in psoriasis patients, with 95% confidence.

Analysis of the association between diagnosis of psoriasis and each of the domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain), separately, adjusted for age, race, schooling, and marital status was done by analysis of covariance. Table 4 shows that the statistical difference was maintained, evidencing that the score in the control group was higher than in the group of psoriasis patients for all the domains.

Comparison of FSFI between the groups with and without psoriasis, adjusted for age, ethnicity, schooling, and marital status (analysis of covariance)

| Mean | Standard deviation | p-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DESIRE | Control | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0.019 |

| Patient | 3.2 | 1.3 | ||

| AROUSAL | Control | 3.9 | 1.8 | 0.001 |

| Patient | 2.6 | 2.2 | ||

| LUBRICATION | Control | 4.3 | 1.9 | 0.014 |

| Patient | 3.1 | 2.6 | ||

| ORGASM | Control | 4.2 | 1.8 | 0.017 |

| Patient | 3.1 | 2.7 | ||

| SATISFACTION | Control | 4.6 | 2.0 | 0.001 |

| Patient | 3.1 | 2.6 | ||

| PAIN | Control | 4.5 | 2.0 | 0.012 |

| Patient | 3.4 | 2.7 |

Sexual dysfunction showed a statistically significant association with the extent of skin involvement (p-value=0.04). However, this association was not observed when analyzing the different lesion sites by means of the chi-square test: genital involvement was present in 25% of the women without sexual dysfunction and in 19% of those with sexual dysfunction, p-value=0.55; ungual involvement in 32.3% of women without dysfunction and in 34.1% of women with sexual dysfunction, p-value=0.868; and involvement of exposed skin areas in 39.3% of women without dysfunction and in 27.9% of women with sexual dysfunction (p-value=0.32).

The association between sexual dysfunction and comorbidities was analyzed by the chi-square test in the psoriasis group (66.7% of women without dysfunction and 79% of women with sexual dysfunction presented comorbidity) and did not show a statistically significant association (p=0.273). As for diagnosis of rheumatic disease, assessed in 69 of the 75 patients included in the study, the chi-square test showed a p-value of 0.91 (53.6% of women without dysfunction and 56.1% of women with sexual dysfunction presented some type of rheumatic disease). Although no statistically significant association was observed between presence of rheumatic disease concurrent with psoriasis and the occurrence of sexual dysfunction, the total FSFI score in women with fibromyalgia was lower (mean 15.4) than in the remaining of the psoriasis group (mean 19.6).

DiscussionThe current study confirmed the impact of psoriasis on QoL, demonstrating that the domains assessed with the SF-36 questionnaire, especially role physical, vitality, role emotional, and mental health are worse in women with psoriasis when compared to healthy controls. These data are consistent with previous studies in the literature.22-23 Al-Mazeedi et al. observed the effect of psoriasis on physical activities and reported that open-air activities and sun-bathing were affected in half of the cases, and light exercises, such as walking, were jeopardized in 77.3% of patients.8 The functional limitation is due mainly to pruritis, irritation, and pain. Palmoplantar psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis add a negative effect to QoL, since they directly affect activities of daily living.8

According to Chiozza, psoriasis patients, more than patients with other dermatologic diagnoses, fear social isolation and rejection and harbor fantasies of abandonment.24 Approximately 26% of psoriasis patients report family tensions resulting from the disease, 50% limit their participation in sports activities, and 40% experience some difficulty in the workplace.25

A recent systematic literature review aimed to assess the prevalence of sexual dysfunction in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, analyzing such factors as depression and extent of the disease in this relationship.26 The review analyzed 4,039 psoriasis patients, of whom 2,567 were men (63.55%) and 1,472 were women (36.45%), with age ranging from 23 to 62 years. In all the studies, patients were assessed as to sexual function based on self-administered questionnaires, and some studies also evaluated psychological aspects and QoL. Although the study populations and questionnaires varied, sexual dysfunction was prevalent in all the studies (ranging from 22.6% to 71.3%).26

Later publications also addressed the subject, with prevalence of sexual dysfunction ranging from 50% to 65%.15,27-31 Prevalence of sexual dysfunction in our patients was high (58.6%), statistically higher than in the control group (38.6%). This difference was maintained in the analysis of the association between diagnosis of psoriasis and each of the domains separately (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain), adjusted by age, race, schooling, and marital status, showing that sexual dysfunction is more frequent in the group of psoriasis patients in all the domains.

Analysis of the psoriasis group showed that patients reporting sexual dysfunction also presented more extensive skin lesions. This same relationship had been observed by Sampogna et al. in 200732, later confirmed by Guenther et al. in 2011,33 although it is not a consensus.8, 13, 25, 30, 34-37

Various factors can impact the quality of sexual life in psoriasis patients, including side effects of medications, increased prevalence of comorbidities,38 lesion site, and symptoms of the skin condition itself, such as pruritis, psychological alterations, and the partner ‘s concerns33

Comorbidities were prevalent in the psoriasis group, as reported in previous studies.39,40 Previous studies have reported a relationship between chronic diseases, especially rheumatic comorbidities, and sexual dysfunction.41,42 However, this relationship was not significant, although patients with fibromyalgia presented lower FSFI scores, which is consistent with the high prevalence of sexual dysfunction described in patients with chronic pain.43 The absence of statistically significant results is probably due to the small numbers in each comorbidity, not allowing an adequate analysis of each condition.

The location of lesions also failed to show a significant association with sexual dysfunction, consistent with the study by Van Dorssen et al.,44 although differing from results reported by other authors, who pointed to genital involvement as an important factor in quality of sexual life.28, 37, 45 A possible explanation could be that the presence of lesion has less influence than local symptoms on quality of sexual life in these patients. Zamirska et al. assessed 93 women for vulvar pruritis or burning sensation (mons pubis, labia majora and minora, and clitoris).46 They found that 44.1% of women presented vulvar discomfort, 19.4%, pruritis, 10.8% burning sensation, and 14% both. However, only 22 women (23.7%) presented psoriatic lesions on the vulva, and 47.3% had a prior history of genital involvement. The authors showed a significant correlation between vulvar discomfort and genital involvement of psoriasis.46

Note that prevalence of sexual dysfunction in the control group (38.6%) is slightly higher than the values found in other studies with healthy Brazilian women, where prevalence varied from 30% to 35.7%.47,48 This could be explained by the different epidemiological profiles of the study groups and the fact that women with chronic diseases, except for arthritis, or chronic drug use were not excluded.

Some limitations to the current study need to be addressed. First, although previous diagnoses of psychiatric disorders such as depression and anxiety were an exclusion factor, no specific psychiatric tests were applied.

Second, corroborating the literature, this group of patients with psoriasis also showed a high comorbidity rate (64%), including diabetes mellitus and hypertension, chronic conditions that are known to be associated with increased sexual dysfunction. Although prior sample calculation was performed to determine the number needed to assess the association between psoriasis and sexual dysfunction, the calculation did not cover the determination of the possible causes of such dysfunction. Thus, to determine the real influence of factors like emotional alterations and comorbidities, especially rheumatic diseases, a larger sample would probably be necessary. In addition, the complete exclusion of women with arthritis from the control group was intended to avoid the possibility of rare cases of psoriatic arthritis preceding cutaneous manifestation from being included erroneously in this group. However, this made the sample intentional, which can also be considered a bias.

ConclusionDespite its limitations, our study was the first of its kind in female Brazilian patients, and the results proved important to confirm the impact of psoriasis on QoL, to identify the domains most affected, and to elucidate the relationship between this disease and alterations in sexual function. The high prevalence of sexual dysfunction in our patients highlights the need for a more comprehensive approach to the health of women with psoriasis, beyond assessment of their skin condition and the extent of the disease, including other QoL issues and specifically sexual function.