Fusariosis is due to inhalation or direct contact with conidia. Clinical presentation depends on host’s immunity and can be localized, focally invasive or disseminated. Given the severity of this infection and the possibility for the dermatologist to make an early diagnosis, we report six cases of patients with hematologic malignancies, who developed febrile neutropenia an skin lesions suggestive of cutaneous fusariosis. All patients had skin cultures showing growth of Fusarium solani complex, and they received amphotericin B and voriconazole. As this infection can quickly lead to death, dermatologists play a crucial role in diagnosing this disease.

Fusarium spp. are fungi found universally in soil, air and plants.1 The infection begins by inhalation of conidia or by direct contact with material contaminated by conidia. In a suitable host, these conidia germinate and invade the surrounding tissue, leading to the disease itself.2

The clinical presentation of fusariosis depends on the immunity of the host and can be localized and superficial, invasive, or disseminated. Patients with deficient secondary cellular immunity and neutropenia, particularly those with hematologic malignancies, represent the majority of cases that evolve to more severe forms of fusariosis. In immunocompetent individuals, the infection can remain superficial, causing onychomycosis and keratitis.1,3

Fusarium spp. are the second most frequent invasive fungal infection in patients with hematologic neoplasms—after only Aspergillus spp.—but are the most common agents of fungemia with skin manifestations (70% to 75% of patients present cutaneous lesions)4,5

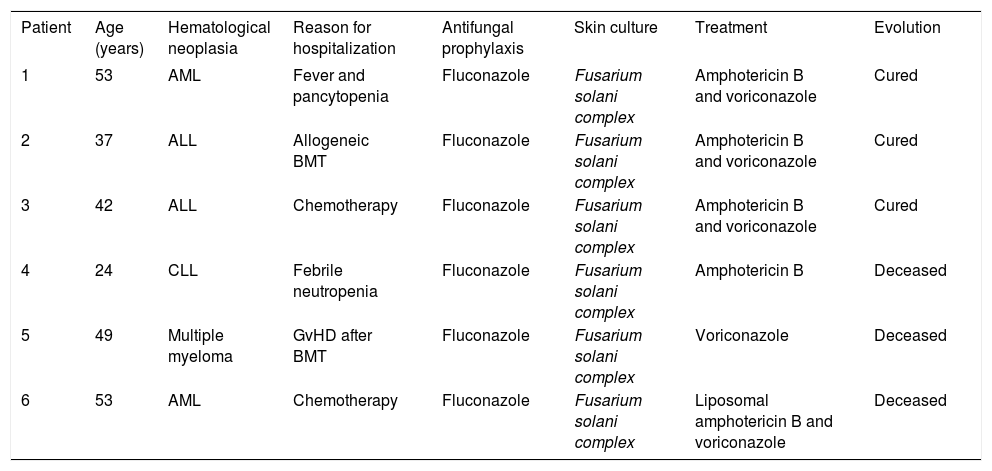

Case ReportDisseminated fusariosis was diagnosed in six patients. The average age was 43 years. All patients had a hematologic neoplasm as the primary comorbidity. Two of them were in chemotherapy, and all of them were neutropenic and submitted to antifungal prophylaxis when the skin lesions arose (Table 1).

Clinical and laboratory information on the patients and evolution of their respective conditions

| Patient | Age (years) | Hematological neoplasia | Reason for hospitalization | Antifungal prophylaxis | Skin culture | Treatment | Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | AML | Fever and pancytopenia | Fluconazole | Fusarium solani complex | Amphotericin B and voriconazole | Cured |

| 2 | 37 | ALL | Allogeneic BMT | Fluconazole | Fusarium solani complex | Amphotericin B and voriconazole | Cured |

| 3 | 42 | ALL | Chemotherapy | Fluconazole | Fusarium solani complex | Amphotericin B and voriconazole | Cured |

| 4 | 24 | CLL | Febrile neutropenia | Fluconazole | Fusarium solani complex | Amphotericin B | Deceased |

| 5 | 49 | Multiple myeloma | GvHD after BMT | Fluconazole | Fusarium solani complex | Voriconazole | Deceased |

| 6 | 53 | AML | Chemotherapy | Fluconazole | Fusarium solani complex | Liposomal amphotericin B and voriconazole | Deceased |

ALL: acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; BMT: bone marrow transplantation; CLL: chronic lymphocytic leukemia; GvHD: graft-versus-host disease

On dermatological examination, patient 1 exhibited erythematous, subcutaneous and slightly painful nodules on the upper limbs (Figure 1A); patient 2 presented diffuse erythematous nodules on the upper and lower limbs (Figure 1B); patient 3 developed a violaceous nodule with a necrotic center in the region of the right metatarsophalangeal joint (Figure 1C); patient 4 presented erythematous and ulcerated nodules on the upper and lower limbs (Figure 1D); patient 5 showed erythematous and subcutaneous nodules on the knee; and patient 6 had violaceous and diffuse nodules, with ulcerated centers covered by necrotic crusts, distributed across the face, trunk and upper and lower limbs (Figures 1E and 1F).

A - Erythematous nodule on the right arm; B - brownish nodule with erythematous halo on the left leg; C - violaceous nodule with necrotic center in the right metatarsophalangeal region; D - erythematous and ulcerated nodules on the legs; E and F - diffuse violaceous nodules, with ulcerated centers and crusted necrotic covering, on the face, trunk and upper and lower limbs

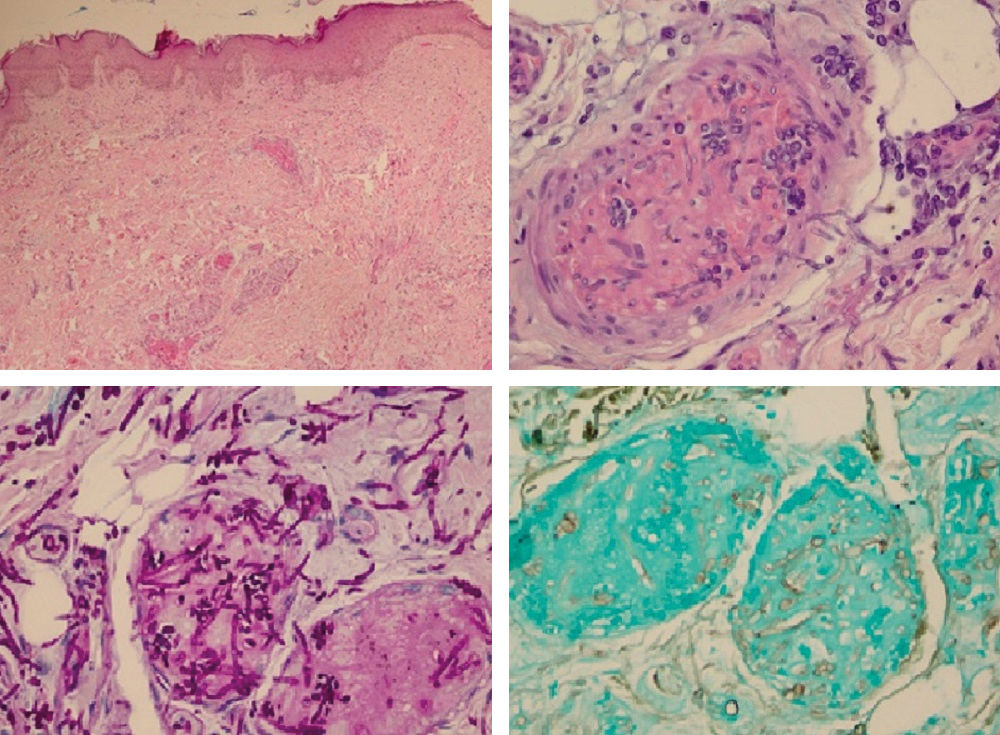

The patients were submitted to biopsy of the cutaneous lesions, and the material was sent for anatomopathological examination and cultures. All cases showed an increase in theFusarium solani complex (Figure 2). The anatomopathological examination revealed innumerable capillary vessels with fibrin thrombi containing numerous hyphae, confirmed by the Grocott and PAS stains (Figure 3). Hemocultures were positive for Fusarium spp. in patients 2, 4, 5 and 6, and patients 1, 3 and 6 showed nonspecific findings on the chest radiograph.

A - Presence of proliferating capillary vessels, with ectasiated lumen filled with fibrin thrombi, in the superficial and deep layers of the dermis (Hematoxylin & eosin, x40); B - in detail, one of the intravascular fibrin thrombi containing numerous hyphae and spores within (Hematoxylin & eosin, x400); C and D - using PAS (C) and Grocott (D) stains, the presence of hyphae and spores in the thrombi is most evident (x400)

Amphotericin B and voriconazole were used together in most cases, except in patients 4 and 5, who were treated with amphotericin B and voriconazole monotherapy, respectively. Three of the six patients died despite treatment, including those that received monotherapy (Table 1). Among patients who recovered, the mean time of onset of symptom improvement was two weeks, especially considering fever and cutaneous lesions.

DiscussionThe most important species in fusariosis is the Fusarium solani complex, due to its greater frequency,2 followed by the species Fusarium oxysporum and Fusarium verticillioides.6 The risk factors for invasive fusariosis are neutropenia, deficient cellular immunity, induction chemotherapy for leukemia, hematopoietic cell transplantation, and graft-versus-host disease—the same risk factors that patients of this series possessed.1,2,5 In these cases, skin and nails must be examined for sites of infection that can serve as gateway for system dissemination.1 Cutaneous involvement can be an important diagnostic clue, since the skin lesions are observable in the early stages of the disease and can even precede positive hemocultures.1,7

Neutropenic patients with disseminated fusariosis typically present fever, myalgias and, in 75% of cases, cutaneous lesions.4 Typical lesions are painful erythematoviolaceous nodules whose centers develop ulceration covered by necrotic crust, observed mostly on the trunk and the extremities, such as those presented by most of the patients in this series of cases.1 As this infection can lead rapidly to the patient’s death, suspected cutaneous lesions should be promptly investigated through skin biopsy for anatomopathological examination and cultures. Fusarium spp. can be isolated in hemocultures in 40% to 60% of cases.8 In this work, 66% of the hemocultures were positive.

A definitive diagnosis requires the isolation of Fusarium spp. from the sites of infection (skin, sinuses, lungs, blood and others).6, 8 These fungi can invade blood vessels—the histopathological findings include branching hyaline septate hyphae in the vessels—and may cause hematogeneous dissemination.8 Their identification in the culture is important, since it is impossible to differentiate between fusariosis and other hyalohyphomycoses by the histopathological study alone. The genus Fusarium is identified in the culture by the multiple crescent- or banana-shaped hyaline macroconidia.8

Antifungal prophylaxis is recommended for immunosuppressed patients, as it can prevent the occurrence of invasive fusariosis in patients with hematologic neoplasms. Varon et al. demonstrated in 2016 that, compared to the use of fluconazole or to the absence of prophylaxis, the use of the antifungal agent voriconazole or posaconazole decreased the incidence of invasive fusariosis in patients with superficial skin lesions positive for Fusarium spp.9

Patient management includes systemic antifungals, surgical debridement of the infected sites, removal of venous catheters in cases of catheter-related fusariosis, and reversal of immunosuppression in the patient.8 Treatment with antifungals is challenging, not only because of the lack of randomized clinical trials, but also because the fungi can be resistant to the drugs.4 There are reports of voriconazole, posaconazole and amphotericin B being used in monotherapy or in combination.2 Some authors recommend combination therapy, such as voriconazole with liposomal amphotericin B, but more studies are needed to explore the real benefit of combination treatment.8, 10

The mortality attributed to infections by Fusarium spp. in immunocompromised patients is high, varying from 50% to 70%, in agreement with the rate found in this series of cases, which was 50%.8 Preventing the dissemination of infection in colonized patients, early diagnosis, and the prolonged use of a combination of antifungals are essential to decrease the mortality rate of this severe infection.10

This series of cases highlights the importance of the dermatologist in the hospital environment and emphasizes their role in the diagnosis of this serious entity, to prevent the fatal progression that occurs in many cases.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of interest: None.