Leprosy, caused by Mycobacterium leprae, is a chronic infectious disease, which may cause permanent damage to peripheral nerves and deformity.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), leprosy cases are classified2 in PB (paucibacillary) or MB (multibacillary) leprosy based on the number of skin lesions: PB leprosy (2‒5 skin lesions), and MB leprosy (more than 5 skin lesions). MB leprosy is mainly caused by the unresponsiveness of cellular immunity against leprosy bacilli,3 and is characterized by high infectivity and functional disability rate. Leprosy disability severely affects the life quality of leprosy patients and may induce psychological problems. However, despite effective measures were extensively implemented, the number of new cases worldwide has remained at almost 250,000 each year. Although leprosy is generally in a low endemic state in northwest China,4 the proportion of MB cases and the rate of disability are still at a high level.

To analyze the sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with MB leprosy in elimination planning areas in Northwest China, three specialized hospitals were included. The medical records of leprosy in province in northwest China from 2004 to 2020 were collected from the Leprosy Management Information System (LEPMIS).

This is an observational and retrospective study, involving 305 cases of MB and PB leprosy cases, collected in the LEMPIS from 2004 to 2020. The variables included gender, nationality, occupation, and others. The statistical significance level was p < 0.05. Logistic regression analysis was used to adjust the confounding variables to determine the independent risk factors of MB leprosy cases.

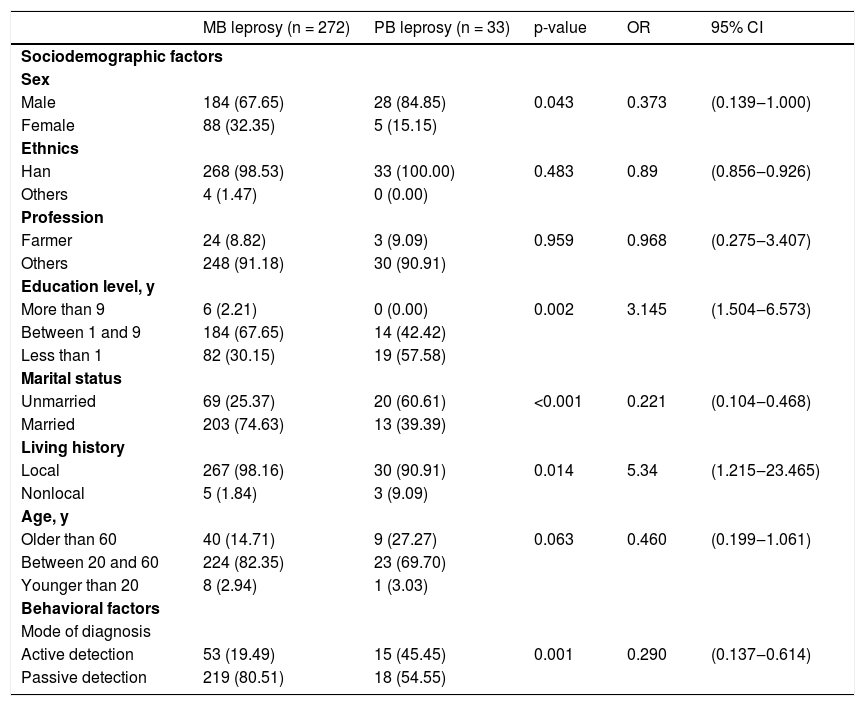

Significant differences in sex and some other variables (p < 0.05) were shown comparing MB and PB cases, as shown in Table 1. Of the MB leprosy cases, 21.32% cases were documented as having less than 5 skin lesions, as shown in Table 2.

Relationship between sociodemographic and behavioral factors and leprosy types.

| MB leprosy (n = 272) | PB leprosy (n = 33) | p-value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | |||||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 184 (67.65) | 28 (84.85) | 0.043 | 0.373 | (0.139‒1.000) |

| Female | 88 (32.35) | 5 (15.15) | |||

| Ethnics | |||||

| Han | 268 (98.53) | 33 (100.00) | 0.483 | 0.89 | (0.856‒0.926) |

| Others | 4 (1.47) | 0 (0.00) | |||

| Profession | |||||

| Farmer | 24 (8.82) | 3 (9.09) | 0.959 | 0.968 | (0.275‒3.407) |

| Others | 248 (91.18) | 30 (90.91) | |||

| Education level, y | |||||

| More than 9 | 6 (2.21) | 0 (0.00) | 0.002 | 3.145 | (1.504‒6.573) |

| Between 1 and 9 | 184 (67.65) | 14 (42.42) | |||

| Less than 1 | 82 (30.15) | 19 (57.58) | |||

| Marital status | |||||

| Unmarried | 69 (25.37) | 20 (60.61) | <0.001 | 0.221 | (0.104‒0.468) |

| Married | 203 (74.63) | 13 (39.39) | |||

| Living history | |||||

| Local | 267 (98.16) | 30 (90.91) | 0.014 | 5.34 | (1.215‒23.465) |

| Nonlocal | 5 (1.84) | 3 (9.09) | |||

| Age, y | |||||

| Older than 60 | 40 (14.71) | 9 (27.27) | 0.063 | 0.460 | (0.199‒1.061) |

| Between 20 and 60 | 224 (82.35) | 23 (69.70) | |||

| Younger than 20 | 8 (2.94) | 1 (3.03) | |||

| Behavioral factors | |||||

| Mode of diagnosis | |||||

| Active detection | 53 (19.49) | 15 (45.45) | 0.001 | 0.290 | (0.137‒0.614) |

| Passive detection | 219 (80.51) | 18 (54.55) | |||

Relationship between clinical factors and leprosy types.

| MB leprosy (n = 272) | PB leprosy (n = 33) | p-value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin lesion | |||||

| None | 8 (2.94) | 5 (15.15) | < 0.001 | 0.170 | (0.052‒0.554) |

| 1 lesion | 6 (2.21) | 7 (21.21) | |||

| 2‒5 lesions | 44 (16.18) | 15 (45.45) | |||

| >5 lesions | 214 (78.68) | 6 (18.18) | |||

| Leprosy reaction | |||||

| No reaction | 233 (85.66) | 30 (90.91) | 0.3 | 0.597 | (0.174‒2.053) |

| I reaction | 15 (5.51) | 3 (9.09) | |||

| II reaction | 20 (7.35) | 0 (0.00) | |||

| Mixed reaction | 4 (1.47) | 0 (0.00) | |||

| Skin smear result | |||||

| Positive | 177 (65.07) | 4 (12.12) | < 0.001 | 13.508 | (4.612‒39.566) |

| Negative | 95 (34.93) | 29 (87.88) | |||

| Nerve damage | |||||

| None | 53 (19.49) | 5 (15.15) | 0.003 | 1.355 | (0.500‒3.678) |

| 1 nerve | 31 (11.40) | 11 (33.33) | |||

| ≥ 2 nerves | 188 (69.12) | 17 (51.52) | |||

| Disability | |||||

| None | 61 (22.43) | 11 (33.33) | 0.007 | 0.578 | (0.266‒1.259) |

| Grade I | 93 (34.19) | 3 (9.09) | |||

| Grade II | 103 (37.87) | 19 (57.58) | |||

| Not clear | 15 (5.51) | 0 (0.00) | |||

These results showed high endemic characteristics of leprosy, suggesting that the delay on leprosy diagnosis5 still exists in northwest China, which led to more serious consequences and disabilities. Leprosy showed a low prevalence trend at this stage, and male patients still accounted for a relatively high proportion of the newly diagnosed cases in each year, which may be related to different genetic susceptibility in different genders. Meanwhile, females got more skin consultations than males, and males may be more easily exposed to leprosy bacilli related to behavioral6 and cultural factors, which may partly explain the dominant position of male cases. The susceptibility of the elderly to MB leprosy may be related to the prolonged incubation period of leprosy bacilli, resulting to delayed response. In addition, the aging of the immune system in the elderly7 was an aggravating factor for infection control. People with higher education8 are more inclined to seek medical services to avoid delaying diagnosis and treatment. Data showed that people with a marriage history are the advantaged group of MB leprosy, which may indicate that close contact in the home was related to exposure to leprosy bacilli, but the we cannot rule out the importance of social contact in disease transmission.

Passive detection was a protective factor for MB leprosy, so it is necessary to increase the publicity and education of leprosy prevention and control knowledge in low-prevalence areas, and to improve the awareness9 rate of the masses and self-care awareness. More than 5 lesions were associated with MB leprosy, which indicated that a high concentration of leprosy bacilli infection can lead to more tissue destruction, more skin damage, and worse deformation. MB cases have a higher probability of grade I or II disability after model adjustment. The incidence rate of Class II disability in the present sample is far higher than the global average of 6% reported by the WHO10 in 2016, which indicated that there is a delay in diagnosis or misdiagnosis in these patients.

This study was based on second-hand data obtained from the LEPMIS, so it has some limitations, such as inconsistent information, prevalence bias and the defect of cross-sectional design. Future longitudinal studies or geographical distribution are desirable to clarify factors related to leprosy.

In conclusion, MB patients were the main infectious source of leprosy, so early detection and treatment can effectively block the transmission of leprosy in the infectious source control link, which is of great significance to reduce the probability of leprosy in patients with disability. This study has shown the epidemic characteristics and regional characteristics of MB leprosy in northwest China, which may be helpful in effectively preventing and controlling leprosy.

Financial supportNone declared.

Authors’ contributionsGe Li: Co-wrote the article; the corresponding author, reviewed the data and results of this article; contributed to interpretation of the data, commented on the manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Chao Li: Co-wrote the article; contributed to interpretation of the data, commented on the manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Qingping Zhang: The corresponding author, reviewed the data and results of this article; contributed to the interpretation of the data, commented on the manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Hong Zhang: Contributed to the collection and acquisition of the article data; contributed to interpretation of the data, commented on the manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Ping Chen: Contributed to the collection and acquisition of the article data; contributed to interpretation of the data, commented on the manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Zhaoxing Lin: Gave guidance on research methods and case review; contributed to interpretation of the data, commented on the manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved the final version for publication.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

The authors would like to thank all participants in the study on leprosy. In particular, the authors would like to express our thanks to the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China and the Health Commission of Shaanxi Province.