Dear editor,

Erythema elevatum diutinum (EED) is a rare chronic cutaneous vasculitis that affects adults between 30 and 60 years of age, with no race or gender predilection. It was initially described by Hutchinson in 1878, however, the name EED was only coined in 1894 by Radcliffe-Crocker et al.1

Its etiology remains unknown and can be associated to deposits of immunocomplexes resulting from chronic antigen exposure or raised levels of circulating antibodies. It can be correlated to streptococcal infections, hematological and autoimmune diseases.2 There are also cases of EED as an initial manifestation of HIV infection.3

The diagnosis of EED is confirmed by histopathology, with the presence of extravascular fibrin deposits, inflammatory infiltrate rich in neutrophils in the blood vessels’ walls and vascular damage.4

The preferred treatment is dapsone. In cases resistant to this drug, colchicine, systemic, intralesional, and high potency topical corticosteroids, sulfapyridine, and niacinamide combined to tetracycline can be tried.1,5 Residual hyperpigmentation with occasional atrophy is common after regression of the lesions.3

A 58-year-old mulatto male patient, with hypertension and diabetes, was referred to the Department of Dermatology with a 5-year history of cutaneous manifestations associated to arthralgia.

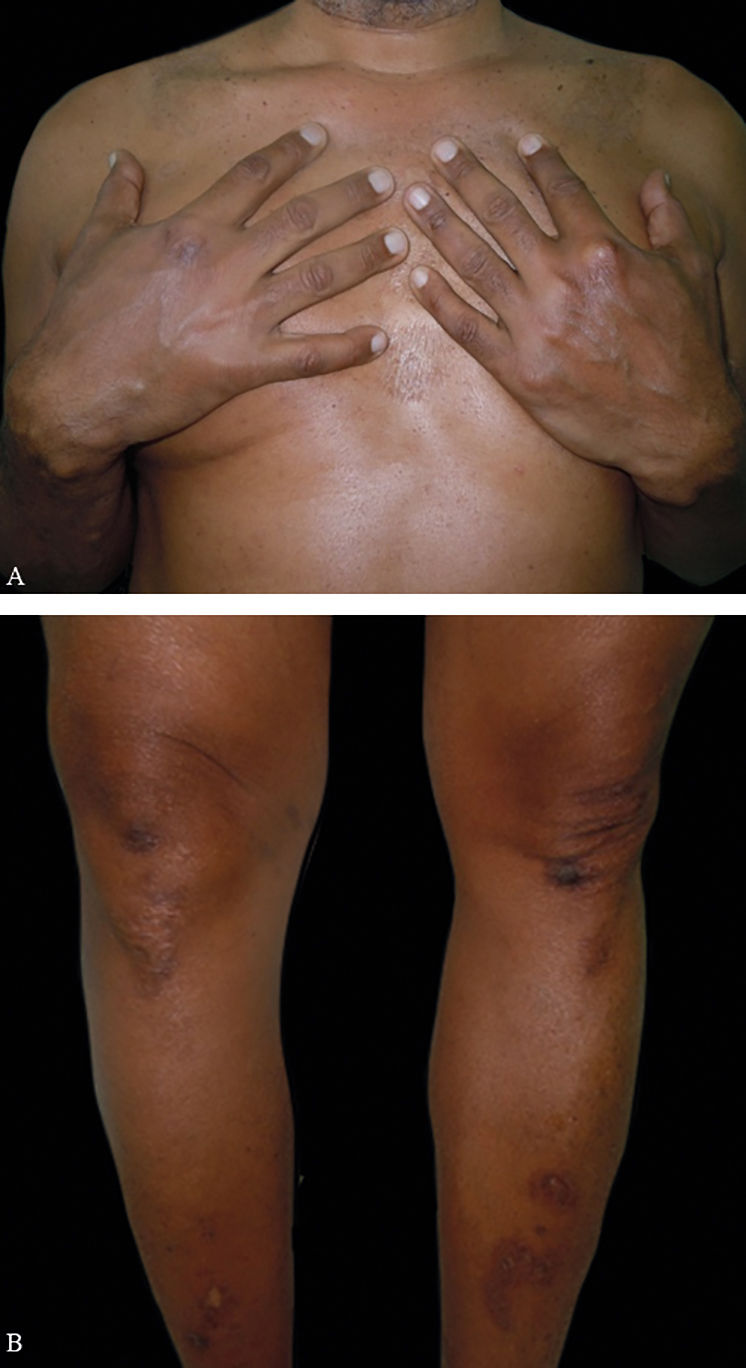

On physical examination, he had firm, symmetrical, and painless erythematous violaceous papules and nodules, with a keratotic surface,on the dorsum of his hands, elbows, knees and ankles (Figure 1).

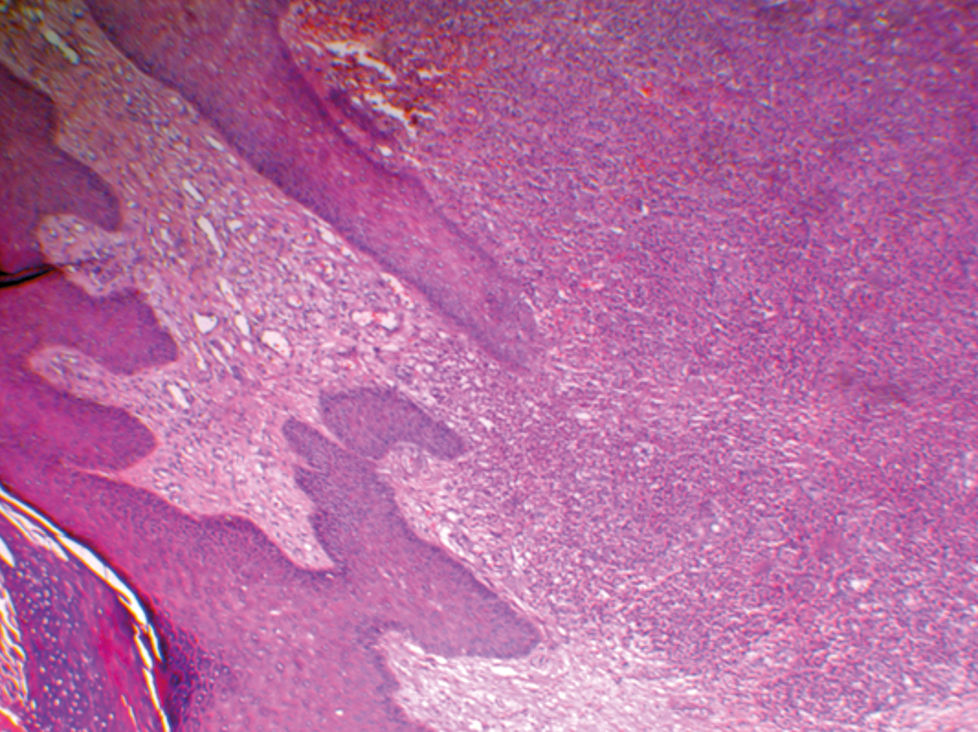

Based on the clinical characteristics, the diagnostic hypothesis of EED was proposed. Histology of the lesion showed changes compatible with leukocytoclastic vasculitis and neutrophilic infiltrate in the dermis (Figure 2).

HIV, hepatitis, VDRL, rheumatoid factor, ANA and lactic dehydrogenase were negative or within normal range.

Dapsone 100mg/day was prescribed after ruling out glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, with clear improvement of the lesions. After six months, the dose of the medication was reduced to 100mg on alternate days. However, some of the lesions on the elbows relapsed, so the daily dose of dapsone was reset. The condition has remained under control, with only residual hyperpigmentation and no side effects of the medication for 1 year (Figure 3).

We highlight that EED is a rare chronic disease, that is manifested by symmetrical erythematous violaceous papules and nodules on the extensor surfaces of the hands, feet, and knees, besides buttocks and lower limbs.1 It can also appear in atypical areas such as trunk, postauricular or palmoplantar regions.4 The lesions have an initial soft consistency, that becomes hardened during their course due to fibrosis.5

Most patients do not present with systemic symptoms.2 Arthralgia is the most common systemic symptom. There are reports of burning pain in the evening in the involved cutaneous areas.2,5

Histology findings vary according to the duration of the disease. In early EED lesions one can find leukocytoclastic vasculitis with neutrophilic infiltrate in the small vessels of the upper and mid dermis.2,3 In advanced stages, the capillary walls can present with fibrinoid necrosis or fibrosis. Extracellular deposits of cholesterol are also a feature of the late stages.5

Differential diagnosis should include Sweet’s syndrome, dermatitis herpetiformis, and rheumatoid neutrophilic dermatitis. Older lesions can be mistaken for tuberous xanthoma, granuloma annulare, rheumatoid nodules, and multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. 2,3

Systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and polychondritis are among the autoimmune conditions that can be associated to EED. Hematologic disorders include IgA monoclonal gammopathy, multiple myeloma, and myelodisplasia.2

Literature shows that the most commonly used treatment is dapsone, from 50 to 150mg/day.3 Its mechanism of action is still unclear. It is believed that there is a stabilization in the lysosomes of the neutrophils or a modification in the deposits of complement (C3).3 EED tends to have a chronic course, despite reports of spontaneous involution after a period that ranges from 5 to 10 years.1,4 Residual hyperpigmentation with occasional atrophy is common with the regression of the lesions.3

Therefore, EED is a rare disease that should be thought of in patients with violaceous papules or nodules, particularly those on the extensor aspects of the limbs.

We highlight the mandatory investigation of possible coexisting autoimmune, hematologic and infectious diseases, including HIV. Therefore, a close follow-up of every EED patient is necessary due to the possible association with severe systemic conditions.

Finally, the main objective of this report is to alert about the possibility of the occurrence of EED, because it is frequently a late diagnosis such as in this case, what is justified by the little knowledge of this condition, particularly among younger practitioners.

Financial support: None.

Conflict of Interests: None.