Epstein-Barr virus is a DNA virus infecting human beings and could affect 90% of human population. It is crucial to take in account that in Latin America, unlike what happens in developed countries, the exposure to the virus is very early and therefore people have a much longer interaction with the virus. The virus is related to many diseases, mainly the oncological ones, and when the onset is in cutaneous tissue, it can present many clinical variants, as well acute as chronic ones. Among the acute ones are infectious mononucleosis rash and Lipschutz ulcers; the chronic presentations are hypersensivity to mosquito bites, hydroa vacciniforme, hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoma, its atypical variants and finally nasal and extra-nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma. Although they are not frequent conditions, it is crucial for the dermatologist to know them in order to achieve a correct diagnosis.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a DNA virus that infects human beings and is related to its oncogenic capacity in different kinds of human neoplasia and, when it affects the cutaneous tissue it origins various clinical processes, which are not frequent but whose diagnose is difficult. On the current article, we present a detailed review of EBV history, the characteristics of its structure and its way of interrelationship with the host, its patterns of activity, latency and reactivation, and the pathological clinical pictures it produces in the skin.

EBV and SkinEBV is a DNA virus classified on Herpesviridae family, Gammaherpesvirinae subfamily, Lymphocrytovirus genus (herpes virus gamma 1) and Human Herpesvirus type 4 species, which infects human beings and is, until now, the first human virus directly involved on lymphoid and epithelial tumors oncogenesis.1 Up to the present, two kinds of EBV varieties were described: 1 and 2, which are distinguished by the genes codifying some of the nuclear proteins.

EBV was discovered in 1964, through electronic microscopy of Burkitt lymphoma cultivated cells by Michael Epstein, Ivonne Barr e Bert Achong. It became the first identified human tumoural virus.2,3 In 1968, EBV showed to be the etiological agent of heterophile-positive infectious mononucleosis (IM). In 1970, EBV DNA was detected on patient's tissues having nasopharyngeal carcinoma. In the 1980s, the association between EBV and non-Hodgkin lymphoma and oral hairy leukoplakia in patients having acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) was discovered. Since then, EBV DNA has been found in tissues of other cancers, including T lymphomas and Hodgkin disease.2 As the technology progress, EBV became the first human virus to have its genome completely sequenced. Human beings are the only known hosts of EBV, nevertheless this virus is genetically related to the viruses found on the oropharynx and B cells of non-human primates of the Old World, suggesting that probably it has evolved from a non-human primates virus.3

Viral Structure and Features of EBVEBV contains a 172kb linear DNA genome whose structure has been appropriately studied and determined. Since the infection of the host cell, the linear genome virus is transformed on a DNA circular episomal structure. EBV genome is composed by a single sequence of long and short domains and repetitive sections referred as repetitive internal parts 1 and repetitive terminal sections. The heterogeneity of the repetitive terminal sections on episomal DNA were explored in order to determine the clonal events of the infection, as well as the number of episomal repetitive terminals remaining unaltered during the replication of the virus on latent phase in an infected cell.

EBV genome is included inside a nucleocapsid, which, in turn, is surrounded by a viral membrane. EBV shows a remarkable tropism for B cells. Before the virus enters in B cells, the glycoprotein of viral envelope, gp350, unites to the viral receptor, CD21 molecule (receptor of C3d complement) on B cells surface.2 An EBV recombinant virus lacking of gp350 can transform B cells with less efficiency, consequently the C3d complement receptor probably is not the only portal through which the virus could enter in B cells, nevertheless it is clearly the most predominant; the antibodies against gp350 blocking the viral link neutralize B cells infection, and soluble forms of C3d or gp350 can do the same.4,5 At least, other 3 union mechanisms proposed do not include neither gp350 nor CD21 (Chart 1). The first one was a demonstration that the viruses treated with immunoglobulin A specific for gp350 united easily to the polymeric receptor of immunoglobulin A. The second union mechanism was the demonstration that, in the absence of CD21, a complex of two additional glycoproteins, gH e gL, can serve as epithelial ligands. EBV stemmed from a B cell can unite appropriately to an epithelial cell CD21 negative, but the recombinant viruses lacking gHgL loose this ability.4 A soluble form of gHgL made on a baculovirus can unite specifically to epithelial cells but not to B cells, and their union can diminish by means a monoclonal antibody specific for gHgL complex. The same antibody can also diminish the viral link. These observations have been interpreted as the existence of a receptor on the epithelial cell for gHgL, useful on the viral link that has not been discovered yet.4

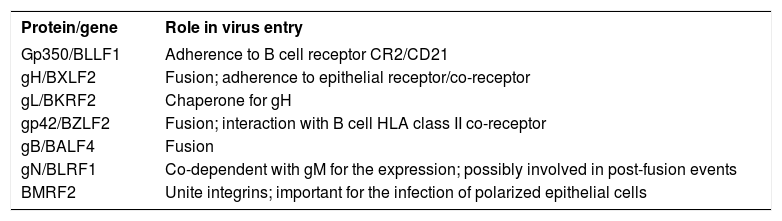

Viral attachment mechanisms

| Protein/gene | Role in virus entry |

|---|---|

| Gp350/BLLF1 | Adherence to B cell receptor CR2/CD21 |

| gH/BXLF2 | Fusion; adherence to epithelial receptor/co-receptor |

| gL/BKRF2 | Chaperone for gH |

| gp42/BZLF2 | Fusion; interaction with B cell HLA class II co-receptor |

| gB/BALF4 | Fusion |

| gN/BLRF1 | Co-dependent with gM for the expression; possibly involved in post-fusion events |

| BMRF2 | Unite integrins; important for the infection of polarized epithelial cells |

Finally, as part of the viral link with B cells, there is viral coating glycoprotein, the gp42 glycoprotein, part of a trimolecular complex including gp85/25 fusion proteins that fix to molecules of the human leukocyte antigen (MHC) class II. MHC class II serves as cofactor for B cells infection. The patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia lack mature B cells, for that, their B cells cannot be infected by the virus, in vitro or in vivo.2This last interaction makes the onset of a catalytic events cascade leading to a viral membrane fusion and allowing the virus to enter the cell.

Epidemiology of EBV InfectionThe infection by EBV on humans generally occurs through the contact with oral secretions. The virus replicates on the oropharynx cells and almost all the seropositive patients present, actively, virus in their saliva. Although the previous studies indicated the virus replicated on the epithelial cells of the oropharynx and the researchers affirmed that B cells were subsequently infected after the contact with these cells, other studies suggest that B cells on the oropharynx could be the primary site of infection.2 When the epithelial cells are exposed to in vitro infection-free cells, we observe a very low level of infection, but when these are associated to infected B cells, the levels of infection increase significantly.

The studies demonstrated the prevalence of EBV infection on virtually the whole human population, affecting more than 90% of the individuals during the two first decades of life over the world. In the developing countries, the primary EBV infections take place during the first years of life and use to be asymptomatic. In developed countries, there is a tendency to late primary nfection, with a higher proportion of infections found in adolescents and young adults, and they manifest clinically as autolimited infections referred as IM.

EBV Infection and The Host ResponseThe main virus way of entry is the upper respiratory tract. The infected B cells are frequently identified on the normal nasopharynx mucosa and the tonsils, since then as part of the normal migration and lymphocyte circulation, these EBV infected B cells spread in the lymph nodes, the peripheral blood and other mucosal sites. EBV positive lymphoid cells have been detected in normal gastric mucosa and other mucous membranes associated to sites with lymphoid tissue on healthy individuals. EBV persists in the infected host in a latent long-term, non-lethal carrier stage. Such carrier stage is perpetuated by a periodic reactivation from the latent phase to the lytic one leading to a low-level dissemination through the virions spreading, from the mucosal surfaces along the host life.

EBV infection produces immune humoral and cellular-type response of the host.2 The host humoral response consists on the production of antibodies against to viral protein structures – the EBV capsular antigen (VCA IgG) and an early antigen (EA- IgG), which do not seem to have a major role on EBV infection control.

In the immunocompetent patient, EBV latent infection is primarily mediated by a population of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, which recognizes epitopes of EBV nuclear antigen 2, 3A, 3B and 3C proteins. These activated T cells are characteristic atypical lymphocytes seen on peripheral blood smear of IM patients. The peripheral lymphocytosis, lymphadenopathy and splenomegaly are expressions of this T cells proliferation. It is believed that activated cytotoxic cells also contribute for the symptoms associated to IM through cytokine secretion as gamma interferon and interleukin 2. On IM, until 40% of CD8+ cells are directed to an EBV replicative protein sequence, while 2% tend to latent protein sequence.2

EBV persistence and its oncogenic potential can be due to many factors, including:

1 - Virus capacity of maintaining its viral genome in the cells, without endangering the host life.

2 - Strategies allowing to evade the host's immune system.

3 - Ability to activate the cell growth control pathways.

EBV has many proteins carrying a sequence and functional homology to many human proteins. It is believed that these proteins have a role in the control of EBV infected cells. EBV codes a cytokine and a cytokine receptor, which can be important in modulating the immune system to allow the persistent infection. BCRF 1 protein shares 70% of its amino acid sequence with interleukin 10; it is an IL10 homologue and allows the viral persistence inhibiting gamma interferon syntesis.2

BARF 1 shows a homology with the colony-stimulating factor 1 and acts as a decoy receptor on blocking cytokine action, resulting in the inhibition of interferon 2 alfa expression by the monocytes. As gamma and alpha interferons inhibit in vitro EBV infected cells growth, BCRF1 and BARF1 proteins could help to evade the immune response during the acute EBV infection or the viral reactivation in latently infected cells.2

EBV codifies at least two proteins that inhibit the apoptosis: EBV protein BHRF-1, homolog to Bcl-2, and LMP 1 human protein that promotes the expression of many cell proteins inhibiting the apoptosis, including Bcl-2 e A20,2 preventing that the infected B cells perform their cell death program.

The immunocompromised patients present high risk of developing B tumors induced by EBV because of the absence of T cell over surveillance, allowing an unrestricted expression of EBV genes as well as an autonomous growth of infected cells (latency type III). On the immunocompromised patient, EBV-associated lymphomas show more restricted forms of latent genic expression, reflecting a more complex pathogenesis involving additional cofactors and happen years after the primary infection. Most of late onset non B-cell type tumors have this origin and probably start from an EBV infected cells clone, which reach the oncogenesis after completing the supplementary changes and growth signs, since a microenvironment, and secondary changes as immune system failure, aberrant genetic events and stimulation of B cell proliferation by other infections.

EBV-infected Burkitt lymphoma cells inhibit the expression of many proteins, which are important to the death generated by cytotoxic T cells. These include the transporting proteins associated to the antigen processing that leads viral peptides from the cytoplasm to the endoplasmic reticulum for antigen presentation, cellular adhesion molecules, allowing the cells to get in touch one to another, and MHC class I molecule that allows cytotoxic T cells to recognize virus infected cells.2

Latent and Lytic Phases of EBV InfectionEBV infects B cells, epithelial cells, natural killer (NK) cells, natural killer T (NK/T) cells, macrophages, monocytes and myocytes. The presence of EBV in secretions of cervix, semen and genital mucosa is also evident.

As characteristic in every herpesviridae, EBV is capable of performing many different programs of genic expression, which are widely categorized inside the genes of a lytic phase and genes of a latent phase. EBV genome can codify around 100 viral proteins including transition factors, replication factors and structural proteins. The expression of EBV-coding proteins varies according on the type, the differentiation and the activation state of the target cell.

Lytic phaseThe lytic phase is that observed in the primary infection. In this phase, the infected cells are destroyed releasing virions. During this phase, the virus is mainly controlled by CD8+ cytotoxic cells, which will kill the infected cells. In normal conditions, this process leads eventually to the virus depuration even not completely. Most of the EBV viral proteins are expressed during lytic replication phase. Two strong transactivators Zta e Rta, coded by BZFL1 and BRLF 1 respectively, were shown to start the lytic replication phase. Studies using mutants lacking Zta or Rta showed that both proteins are necessary to the virus production.5

Latent phaseEBV persists on a latent phase in memory B cells. Although some researchers suggest that EBV could enter directly in the epithelium after the initial infection, there is a strong evidence that the latent phase occurs only in B cells and not in the oropharyngeal epithelium.6

It is generally thought that infected memory B cells carrying EBV in the latent phase can persist forever in the host, in the tonsils or in the peripheral circulation. To escape successfully from the immune response, the virus passes by many genetic and molecular changes. Concerning the EBV genoma, its DNA turn into circular episoma during the latency and is replicated by the host DNA polymerase and then given to daughter cells during the cell division process.6

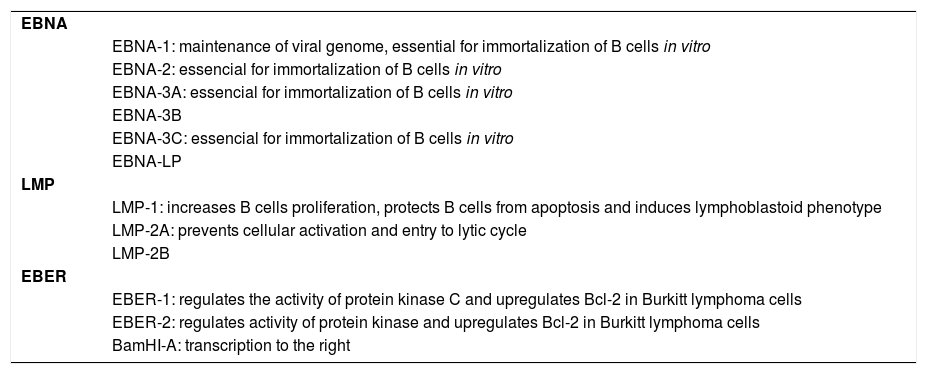

From almost 100 genes expressed during the replication, only 10 are expressed on the latent infection phase2 and these include 6 nuclear antigens (EBNA 1, EBNA 2, EBNA 3a, EBNA 3b, EBNA 3c and EBNA leader protein/EBNA LP), 3 latent membrane proteins (LMP 1, LMP 2a and LMP 2b), two noncoding RNA molecules (EBER 1 e EBER 2) and transcripts from the BamH1-A region (BART transcripts). The genetic studies with recombinant EBV showed that EBNA 3a, EBNA 3c and LPM 1 are essential for the immortalization inside in vitro B cells. For a selective limiting expression during latency, EBV diminish the number of viral proteins that normally could be recognized by cytotoxic T cells (Chart 2).2

Antigens expressed by EBV during latency phase to escape the host immune response and their main roles

| EBNA | |

| EBNA-1: maintenance of viral genome, essential for immortalization of B cells in vitro | |

| EBNA-2: essencial for immortalization of B cells in vitro | |

| EBNA-3A: essencial for immortalization of B cells in vitro | |

| EBNA-3B | |

| EBNA-3C: essencial for immortalization of B cells in vitro | |

| EBNA-LP | |

| LMP | |

| LMP-1: increases B cells proliferation, protects B cells from apoptosis and induces lymphoblastoid phenotype | |

| LMP-2A: prevents cellular activation and entry to lytic cycle | |

| LMP-2B | |

| EBER | |

| EBER-1: regulates the activity of protein kinase C and upregulates Bcl-2 in Burkitt lymphoma cells | |

| EBER-2: regulates activity of protein kinase and upregulates Bcl-2 in Burkitt lymphoma cells | |

| BamHI-A: transcription to the right |

The EBNA 1 protein is a phosphoprotein capable of binding to viral DNA and maintain EBV genome in the host cell as a circular episoma. It is also required for the replication and maintenance of the viral genome and plays a central role in maintaining the latent infection and the cellular immortalization. The mutant virus EBNA1 demonstrated to be 105 times less infectious than its savage counterpart.5

EBNA 2 regulates the expression of the viral and cellular genes that contribute to the growth of B cells and their transformation, including those coding LMP 1, LMP 2, CD 21 and CD23. C-MYC oncogene seems to be another EBNA 2 important target and therefore it could affect subsequently a EBV-induced B cell proliferation.

The three members of EBNA 3 family are in charge of the transcription and EBNA 3a and EBNA 3c are crucial for in vitro B cells transformation. Although it is not crucial for in vitro B cells transformation, EBNA LP interacts with EBNA 2 to inactivate tumor suppression genes p53 and Rh.

The virus study in which the genes of proteins EBNA 2 or EBNA 3c were deleted led to the conclusion that these products were crucial for the B cell immortalization in vitro, while EBNA 3a protein seems to contribute only for the initial process of B cell immortalization.5

LMP 1 is the bigger EBV oncoprotein and is vital for proliferation and maintenance of B cells induced by EBV in vitro.5 Functionally, LMP 1 acts simulating CD40 and inducing cellular signs, which are critical for B cell transformation. The oncogenic potential of LMP is lately related to its ability of recruiting cellular genes resulting in an activation constituting of nuclear factors and adhesion molecules overregulation, cytokine production and B cell proliferation (Chart 2).

LPM 2 maintains and prevents EBV reactivation in infected cells on latent phase in the bone marrow.

Although it was thought that the latency phase would be mediated by the latent genes mentioned above, B cells exposed to a virus lacking of BALF 1 and BHRF 1 have died of apoptosis immediately after the infection. Therefore, the concept of latent genes, or viral genes with dual function as well lytic as latent, could extend to these two Bcl-2 viral homologs. It is also important to mention that the viruses, lacking only of one of these genes, were indistinguishable from the savage-type viruses, suggesting that both BALF 1 and BHRF 1 interfere with the cellular apoptosis program in two different ways or that a high level of antiapoptotic proteins is necessary to counteract the cellular death.5

ReactivationIn physiological conditions, the immunological control maintains the number of infected cells on a very low level; although in certain circumstances (mainly different forms and degrees of immunosuppression) virus reactivation occurs, and it enters the lytic phase again.

Even if B cells are the kind of cells compromised on latency and, therefore, they are the site where the virus survives and avoids the immune response, the change from the latent phase to the lytic one was exceptionally reported and is more observed on epithelial cells. It is still unclear how this occurs.

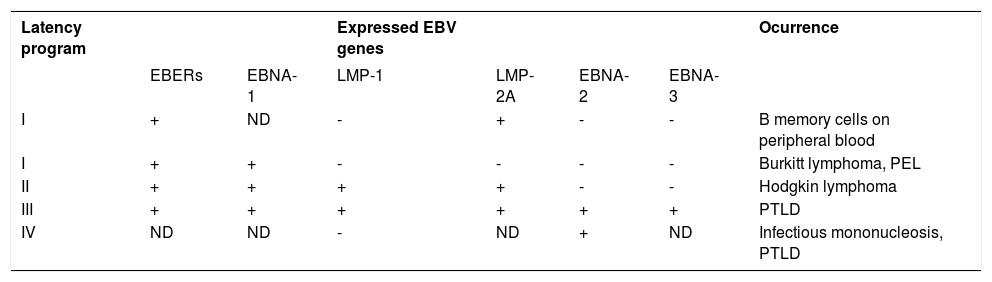

Latency PatternsLatency III ProgramThe expression pattern of latent EBV genes observed in the lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) is known as latency III pattern of EBV infection and is characteristic of the majority of lymphomas in post-transplant patients. The total set of coded EBV proteins is detected by the LCL.7,8 These cells divide the products in messenger RNA strands, which are translated in EBNA 1 to 6, and besides, the virus codes LPM 1, LPM 2a and LPM 2b. Latency III program is only expressed in B lymphocytes. LPM 1 has a strong impact on B cell phenotype, inducing the activation of markers like CD23, CD30, CD39 and CD70 and costimulating and adhesion molecules, leukocyte function-associated molecule 1 (LFA-1; CD11a/18), LFA-3 (CD58) and the intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1; CD54), which increase their immunogenicity with T cells.7 For these reasons, the cells expressing latency III pattern can exist during the acute phase of primary infection, before the T cell specific response against EBV develops.

Latency type I ProgramIt is characterized by the expression of a nuclear protein, EBNA 1, the only protein consistently observed in cells derived from tumors of the Burkitt lymphoma type together with EBER and BamH1-A transcripts.7,8 This kind of latency is expressed in healthy carriers and has a limited repertory of genetic expression, which prevents viral replications and proliferations capable to kill the host cells. The eventual result of EBV infection in an immuno-compromised patient leads to a response type T, CD 8+ in which predominate targets of EBNA 3a/b/c epitopes, which are a subset of latent infection proteins. EBNA 1 is not the target of this T cytotoxic response, allowing that the EBV infected cells escape from the immune vigilance. The T cytotoxic cells do not recognize EBNA 1 because the expression of alanin glicin repeats creating an inhibiting sign that interferes and restrains the antigen processing and the presentation of the MHC class I.

Latency type II programFinally, the latency program type II was originally identified in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and, subsequently, found in cases of Hodgkin lymphoma associated to EBV.7,8

This kind of latency was divided in two subtypes, type II A and type II B. Although both latencies share many common findings, they are distinguished by the lack of expression of two proteins quite necessary for cellular transformation: EBNA 2 is absent in latency type II A and LPM 1 is absent in latency type II B.

Latency type II AIn this kind of latency pattern, the expression of EBV gene is limited to EBNA 1, LPM 1 and LPM 2. It was initially identified in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and NK-cell lymphomas.

Latency type II BThis kind of latency program is characterized by the expression of all EBNA proteins and the lack of LPM 1. This pattern was primarily detected in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia type B (Chart 3).

Expression of EBV latent genes associated with latency programs

| Latency program | Expressed EBV genes | Ocurrence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBERs | EBNA-1 | LMP-1 | LMP-2A | EBNA-2 | EBNA-3 | ||

| I | + | ND | - | + | - | - | B memory cells on peripheral blood |

| I | + | + | - | - | - | - | Burkitt lymphoma, PEL |

| II | + | + | + | + | - | - | Hodgkin lymphoma |

| III | + | + | + | + | + | + | PTLD |

| IV | ND | ND | - | ND | + | ND | Infectious mononucleosis, PTLD |

ND, not determined; PEL, Primary effusion lymphoma; PTLD, Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorder; +, expressed; -, not expressed

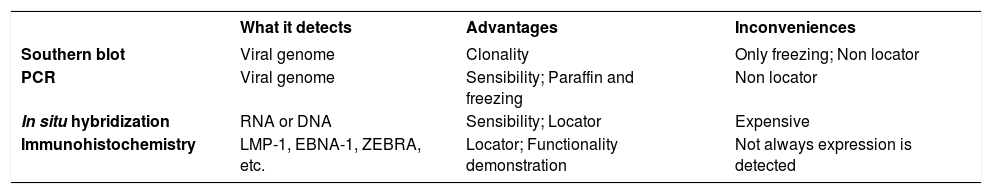

Southern blot technique is useful for EBV detection, especially for the investigation of viral clonality. Nevertheless, the sensibility is lower when it is compared to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Differently to Southern blot, PCR can be used in paraffin-embedded tissues, besides it allows the viral subtypification and the LMP-1 delection evaluation. However, neither Southern blot nor PCR allow the identification of which cells are infected by the virus.6

Moreover, during the latent infection, the EBERs are highly transcribed and the nucleus often contains more than 10 copies of the virus. The EBER detection by in situ fluorescent hybridization showed to be a reliable method and was recommended as the best method for detecting latent EBV in biopsies. Some inconvenient are the positivity of non-tumoral lymphocytes carrying latent EBV and false positive through some contaminants as mucin, yeasts and plant material.6

There are commercial antibodies against LMP-1 and EB-NAs, nevertheless they show to have low sensibility. For example, LMP-1 expression rate detectable by immunohistochemistry varies from 50 to 80%. On the other hand, LMP-1 can also be detected by hybridization of paraffin-embedded tissues with LMP-1-SERS method, which showed to be superior than conventional immuno-histochemical staining for LMP-1, and similar to in situ hybridization for EBER (Chart 4). 6

Molecular techniques used for EBV detection

| What it detects | Advantages | Inconveniences | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Southern blot | Viral genome | Clonality | Only freezing; Non locator |

| PCR | Viral genome | Sensibility; Paraffin and freezing | Non locator |

| In situ hybridization | RNA or DNA | Sensibility; Locator | Expensive |

| Immunohistochemistry | LMP-1, EBNA-1, ZEBRA, etc. | Locator; Functionality demonstration | Not always expression is detected |

EBV is a virus very difficult to detect by auxiliary studies and, therefore, it is very complicate to determinate its participation on the pathogenesis of the cutaneous diseases. On the other hand, the occurrence of these diseases is also not very common in the cutaneous pathology but, due to its unusual presentation and possible complications, it is important to recognize them.

The forms of presentation can be divided into two: the acute forms and the chronic ones.

Acute Forms Infectious MononucleosisDuring childhood, EBV primary infection is usually indistinguishable from other viral diseases. In some patients, it manifests by non-painful growth of lymph nodes and proliferation of oropharyngeal lymphoid tissue. The oropharyngeal infection results from an localized early lytic infection followed by infection of circulating B cells. The appearance of heterophile antibodies in the serum is a critical marker for the diagnosis and is a result of B cell activation. The heterophile antibodies are composed by IgG e IgM antibodies directed against capsule antigens, then there is a seroconversion against EBV nuclear antigens.

In adolescents and young adults, EBV infections often result in an IM. They get the infection through transmission of oropharingeal secretions and, after incubation period (30-50 days), the disease is expressed clinically in more than 70% of exposed adolescents.9 It is an autolimited lymphoproliferative disease, with several days of fever (2 - 3 weeks), pharyngitis associated with exudate (30% cases) and cervical adenopathies. During prodomal phase, the patient presents weakness, anorexia, fatigue, headache and fever. The presence of splenomegaly is variable, detectable on the physical examination in more than 17% and in radiological imaging in almost 100%. The infrequent manifestations include obstruction of the airways, abdominal pain, rash, jaundice, hepatomegaly and eyelid edema. The cutaneous lesions are present in approximately 5% of the patients; the rash can be macular, petechial, scarlatiniform, urticariform or erythema multiforme type.9 In 90 to 100% of patients consuming ampicillin on the previous 10 days, a maculopapular exanthema is evident. Some cases with amoxylin and beta-lactam antibiotics have also been described. In most of IM patients, the disease is caused by an EBV primary infection but similar symptoms can occur in cytomegalovirus infection and a syndrome caused by hypersensitivity to sulfones, anticonvulsants, allopurinol and other drugs. IM complications are neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, splenic rupture, airways obstruction by tonsillar hypertrophy, central nervous system impairment and fulminant hepatitis.

Patients having a complete expression of the disease contain virions from 0.1% to 1% of peripheral B cells. These infected B cells from IM patients express a type III latency pattern. Interestingly, HLA I polymorphism seems to predispose some patients to MI development on an EBV primary infection, suggesting that this genic variation in T response can influence in the primary infection nature and viral persistence level.

From the histological point of view, the lymphatic tissue and the extranodal lymphatic tissue, during IM, show secondary germinal centers having a remarkable expansion of type B immunoblasts concerning the paracortical areas. Mononuclear and binuclear immunoblasts, that occasionally look Reed-Sternberg cells, are frequently present. Besides, these immunoblasts can express positive markers for CD 30. This so florid type of proliferation is not easily differentiated from lymphomas taking only in account the morphology and the immunophenotype, therefore the clinical correlation is very important.

Lymphocitosis presence >= 50%, atypical lymphocytes >= 10% and positive heterophile antibodies allow to recognize adequately IM cases caused by EBV.7

Lipschutz Ulcers (Acute Genital Ulcer Non-Related to Sexually Transmitted Diseases)Lipschutz ulcers, also known as ulcus vulvae acutum, was primary described by the German dermatologist Lipschutz, in 1913. He subdivide them in three subtypes based on clinical findings, which would correspond to what is known today as herpetic infection ulcers, Behçet syndrome, and those so-called vulvar acute ulcers, which can have a multiple etiology. The relation with EBV was suggested by Brown and Stenchever and, in 1984, by Portnoy et al.

They are painful ulcers on external genitals, generally present in female adolescents with with a mean age of 14.5 years old. They affect about 10 to 30% of female adolescents.3

Concerning the ethiology, although there is evidence demonstrating that acute genital ulcer can be a EBV primary infection manifestation, there are published cases associating it to other infections like cytomegalovirus, influenza A virus, influenza B virus and adenovirus, mumps virus, Salmonella paratyphi, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and Lyme disease.10 It is believed that the ulceration is due to an EBV viremia complication during acute infection, which arrive to genitals via lymphocytic infiltration, blood circulation, or autoinoculation with saliva or cervicovaginal fluid. Once in the genital mucosa, one of the following mechanisms produces the ulceration: cytotoxic immune response, deposition of immunocomplexes or direct cytolysis, consequence of the viral replication in the wall and endothelium of blood vessels. That would produce a lymphocytic vasculitis or, finally, a cytolysis process due to EBV replication in keratinocytes with a reactive inflammatory response secondary to the liberation of particles in the stroma.

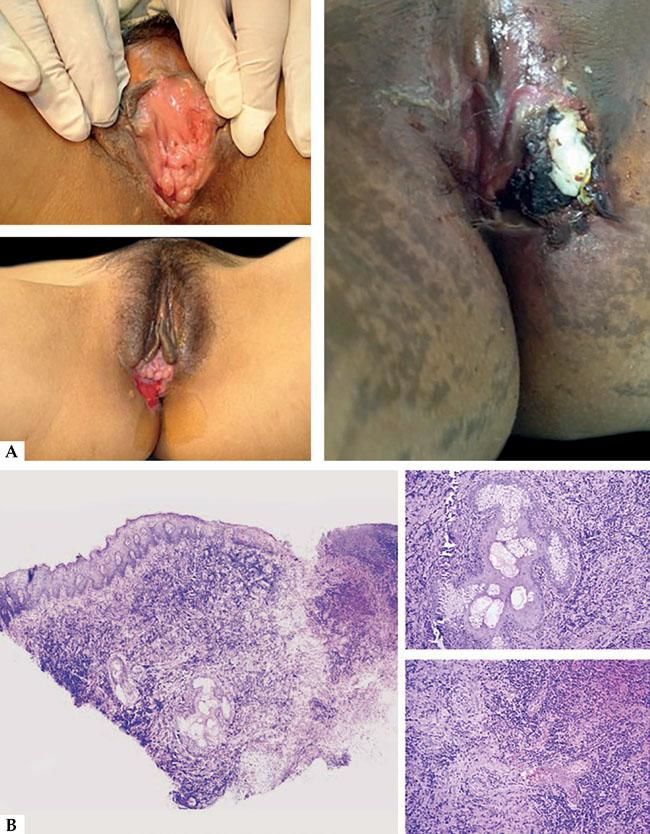

Clinically, it affects adolescents or young females sexually non-active and can be preceded by flu symptoms or similar to IM as fever, fatigue, anorexia, headache.3,10 It is characterized by the sudden appearance of one or many vulvar ulcers. The ulcers are large (>1cm) and deep, with a purple-red halo and a necrotic base recovered by a greyish exudation or a grey-black adherent eschar. Usually it affects the posterior commissure (frenulum) of labia minora but can extend to the labia majora, the perineum and the lower part of the vagina, and it is characteristic the simmetric bilateral involvement, described as mirror image.10 Other signs can be present like swelling of lips and inguinal adenopathy. The distant lymph-adenopathy is frequent.3,10 Severe pain and dysuria are constantly reported.10 In approximately 70% of the cases, it is reported an oral impairment like thrush. Lipschutz ulcers usually appear in single episodes, differently from those caused by herpes simplex virus.3 The healing of the acute lesion happens from 2 to 6 weeks after and does not leave scars.10 Laboratory studies, as well as culture tests, are completely negative and become positive after 15 days of infection.

The differential diagnosis is extensive and includes any acute genital ulcer having an infectious origin or venereal: syphilis, herpes simplex virus, lymphogranuloma venereum and chancroid; or non-venereal: cytomegalovirus, Brucella; as well as non-infectious origin: Crohn disease, Behçet syndrome, pemphigus vulgaris, lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, idiopathic aphthous ulcer, fixed drug eruption, erythema multiforme.11

Basically, it is an exclusion diagnosis and can be established fulfilling 5 of the following major criteria and 1 or 2 of the minors:12

- 1.

Presentation as a first outbreak of acute genital ulcer

- 2.

Under 20 years old

- 3.

Absence of sexual contact during the last three months

- 4.

Absence of immunodeficiency

- 5.

Acute course of genital ulcer (sudden onset and cure with no scars within 6 weeks)

Concerning the symptoms of genital lesions, the minor criteria can be presented on the 2 following patterns:

- 1.

One or many painful, well delimited and deep ulcers with necrotic and/or fibrinous center

- 2.

And a bilateral "kissing" pattern

Histologically, it is characterized by the presence of an acute ulcer with dense infiltrates in the base, a dense mixed inflammatory infiltrate and the presence of a lymphocytic vasculitis. The immuno-histochemical and hybridation study can be negative in 60% of the cases. The diagnosis can be confirmed serologically after 15 days. The treatment is symptomatic with topical corticosteroids or short courses of oral prednisone (Figure 1).3

Gianotti-Crosti Syndrome (GCS)GCS, syndrome or papular acrodermatitis of childhood is an autolimited eruption of acral location and acute course with generalized lymphadenopathy. The syndrome is characterized by a papular and monomorphic eruption, with symmetrical edematous papules tending to be asymptomatic. It is located in cheeks, back of the hands, buttocks and extensor aspects of arms and thighs in children from 2 to 6 years old.13 It is considered a non-specific cutaneous response to many infectious agents, specially viruses, the EBV is one of the most frequently associated. GCS can be the manifestation of an EBV primary infection or the result of a endogeneous viral reactivation. Other ethiological agents include hepatitis B virus, cytomegalovirus, adenovirus, coxsackievirus, parainfluenza virus, poxvirus, parvovirus B19 e HHV-6.13

The association of EBV primary infection and GCS can be diagnosed only by serology. From the histological point of view, the findings are unspecific and include focal parakeratosis, mild spongiosis, superficial perivascular infiltrate, red blood cell extravasation and edema of the papillary dermis. This last was emphasized as being prominent in GCS cases associated to EBV and is due to the high number of cytotoxic T cells, which compose the inflammatory infiltrate.13 There is still no evidence of viral antigens or particles with the aid of in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry.

Chronic Active Infection by EBVA group of patients presents recurrent cases of IM for more than 6 months. This condition is known in the literature as chronic active EBV infection (CAEBV) and is considered a lymphoproliferative disorder that occurs mainly in children.6 By definition, this disorder occurs in patients with no immunodeficiency or autoimmune diseases. Virelizier et al. have described it for the first time in 1978 as an atypical disease associated to a serological evidence of EBV persistent infection. It is a rare disease in United States and in Europe but it occurs more frequently in Asia and South America. Unlike the diseases associated to EBV, the majority of CAEBV cases in Asia and South America are due to the presence of EBV in T or NK cells, and for this reason the disease has an aggressive course associated to a high mortality and morbidity with high levels of EBV viremia and an abnormal pattern of humoral response.14 On the contrary, EBV is generally found in B cells of CAEBV patients in United States, for this reason the disease follows generally an innocuous course with a rare progression to a lymphoproliferative disorder type T.14 This disease is defined by:

- 1.

Onset as an acute EBV disorder, with very high levels of antibodies against EBV or EBV DNA in the blood.

- 2.

Histological evidence of organic infiltration with virus infected cells.

- 3.

Detection of EBV protein or nucleic acid in tissue CAEBV has been reported as a clonal, oligoclonal or polyclonal disease.

Emendar com frase acima abnormalities were noted in CAEBV. The patients with T or NK cells disease have high levels of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL 1 beta, interferon gamma, IL 10, IL 13, IL 15, tumor necrosis factor alpha and transforming growth factor beta.14

The accumulated evidence indicates that the central pathogenic finding of a severe CAEBV is a clonal expansion of T or NK cytotoxic cells. This clonal expansion was associated to clonal anomalies of EBV genome and frequent development in T lymphoma. This last presentation includes hydroa-type lymphoma in children. Thus, over time, CAEBV is being considered as a NK/T lymphoproliferative disorder rather than a simple aberrant response to EBV infection.

Most of patients presents fever, hepatic dysfunction and splenomegaly. Approximately half of patients has lymphadenopathy, thrombocytopenia and anemia; 20 to 40% of patients have symptoms as hypersensitivity to mosquito bites, rash, hemophagocytic syndrome and coronary artery aneurysms. Less often, they present calcification of basal ganglia, oral ulcers, lymphoma, interstitial pneumonia and central nervous system disease. The presence of thrombocytopenia, onset at 8 years of age or more, and EBV infection of T cells have associated to a worse prognosis. The death generally is due to a hepatic failure, malignant lymphoma and opportunistic infections.14

CAEBV has two different clinical manifestations depending on whether T or NK cells are those predominantly infected in peripheral blood. T-type infections characteristics are high fever, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly and high titers of EBV antibodies. In contrast, NK-type infections show a granular lymphocytosis, hyper-sensitivity to mosquito bites and high IgE titers.

Patients with CAEBV generally have high titers of antibodies against viral capsule antigen and diffuse/restrictive early antigen. Anti-VCA IgM or anti-VCA IgA antibodies are usually negative in healthy individuals, but sometimes are positive in CAEBV patients. Anyway, high titers of antibodies against these EBV proteins are not necessary for CAEBV diagnosis. In addition, many of the patients with CAEBV are EBNA-antibody positive but 20% can be negative. In brief, there are not highly sensitive or specific serological tests for CAEBV diagnosis.

The presence of EBV on the affected tissues or in peripheral blood is essential for CAEBV diagnosis. The methods for EBV detection can be carried out by the detection of antigens related to peripheral tissues or blood, by immunofluorescence or immunohistochemistry, analyzing Southern blot hybridization or finally coding RNA 1 fragments in EBV infected cells.

Hypersensitivity to Mosquito Bite (HMB)HMB was described initially in 1938 in a patient from Florida, USA. In 1990, Tokura et al. described an HMB patient whom 50 to 60% of mononuclear cells of peripheral blood were large granular lymphocytes as NK cells. On the other side, HMB was present in a considerable number of patients with EBV active chronic infection. Finally, it is concluded that HMB occurs in close association with NK cells disease, where monoclonal EBV infects the cells. For this reason, nowadays it is known as “HMB-EBV-NK disease”.15

The HBV is a disease generally associated to EBV chronic infection and, in some cases, can precede this one. It is a cutaneous disorder characterized by an intense cutaneous local reaction presented as erythema, blisters, ulcers and scar tissue formation, followed by systemic symptoms as fever, lymphadenopathy, hepatic dysfunction and hemophagocyt syndrome after mosquito bite. The target cells of latent EBV infection in HMB are NK cells and T NK cells.16 The mechanism of this process would be due to the stimulation by the mosquito saliva to infected cells.

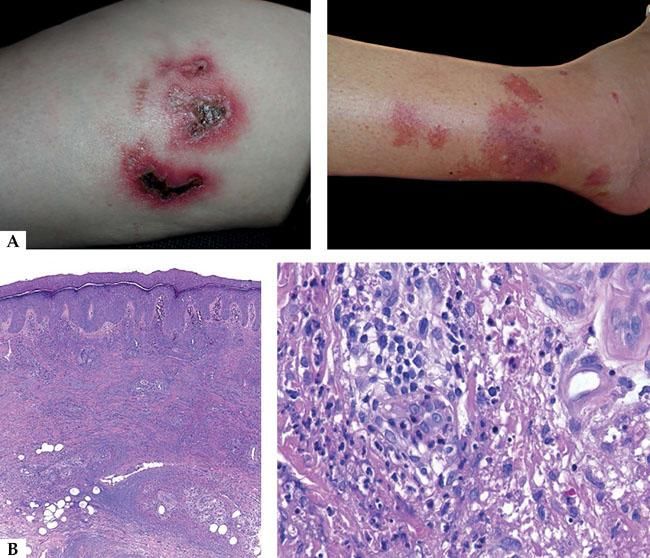

Clinically, three stages are observed: initially there is an overreaction to mosquito bite characterized by erythema, blisters, ulcers and scar tissue formation; later the patients develop many episodes of systemic symptoms as fever, lymphadenopathy and hepatic dysfunction. These patients have potential risks of leukemia or lymphomas and some of them have already the mentioned diagnoses, including on the first episode of HMB. Finally, one of the more severe complications is hemaphagocytic syndrome, which is produced on the final stages.15 The majority of patients has under 20 years old, in average 6.7 years old and it is important to distinguish it from allergic reaction to mosquito bite taking in account the severity of cutaneous lesions and the associated systemic symptoms (Figure 2A).

DNA EBV levels in the peripheral plasma cells and mononuclear cells are usually high in these patients, compared to healthy patients. Besides, many of HMB patients have high titers of antibodies against lytic proteins as viral capsule antigen and early antigens, suggesting that the repetitive phenomenon of EBV reactivation would be a promoter event.

Histologically, it is observed in the sites of mosquito bite reaction, a dense infiltrate of T and NK cells with superficial and deep perivascular predominance, with cytotoxic molecules and a low proportion of EBER-positive cells. It has been shown that T cells would be CD4 and, by in vitro studies, it is observed that, when CD4 and NK cells are put together, they induce the expression of EBV lytic proteins in NK cells. Therefore, CD4 lymphocytes are important for primary reactions to mosquito bites and can play an important role in the reactivation of latent EBV infections on NK cells. Recently Sakakibara et al. suggested the presumed involvement of mosquito-specific IgE and CD203c+ cells, corresponding to basophiles and/or mast cells, in the sever cutaneous reactions to to mosquito bites in HMB.11 Although the specific immune response mediated by T CD4 cells seem to be an important triggering, the subsequent response of cytotoxic T cells against lytic cycle proteins can be more responsible for the pathogenesis of IM-type symptoms in these patients (Figure 2B).

Hydroa Vacciniforme (HV)‘Hydroa’ derives from the Greek hýdor that means ‘water’, reflecting the vesicular nature of the dermatosis, and ‘vacciniforme’ derives from the Latin vaccinum, ‘similar to vaccin’, related to its tendency to leave a scar.17

In 1862, Bazin carried out the first description of this disease. Halasz and Goldgeier in 1983 documented the triggering role that UVA radiation has in this disease.17 In 1999, it was reported that HV was a childhood photosensitive dermatosis mediated by EBV-infected T cells, occuring in 3 to 20% of the dermal infiltrate, and the amplification by PCR demonstrated the evidence of DNA EBV sequences on biopsy specimens. In many skin biopsies, reactive T cells contain cytotoxic molecules as TIA-1 and granzyme B. Although there are not serological abnormalities, the amplification by PCR in real time demonstrated high levels of DNA EBV in the mononuclear cells of peripheral blood comparing them with the levels of healthy voluntary people. The amount of DNA EBV, anyway, was lower than in those with CAEBV. These data indicated that a small amount of EBV infected cells that circulates in the blood has no hematological abnormalities and these EBV infected cells would migrate to the sun-exposed skin along with T lymphocytes.

HV presents generally during the first life decade, however a late onset was documented. Gupta et al. identified a bimodal distribution of the illness onset between 1 and 7 years old and other one between 12 and 16 years old. According to gender, females present an earlier onset (in average 7 years old) than males (9 years old); concerning the length of the disease, males presented a longer duration (11 years) than females (5 years).17

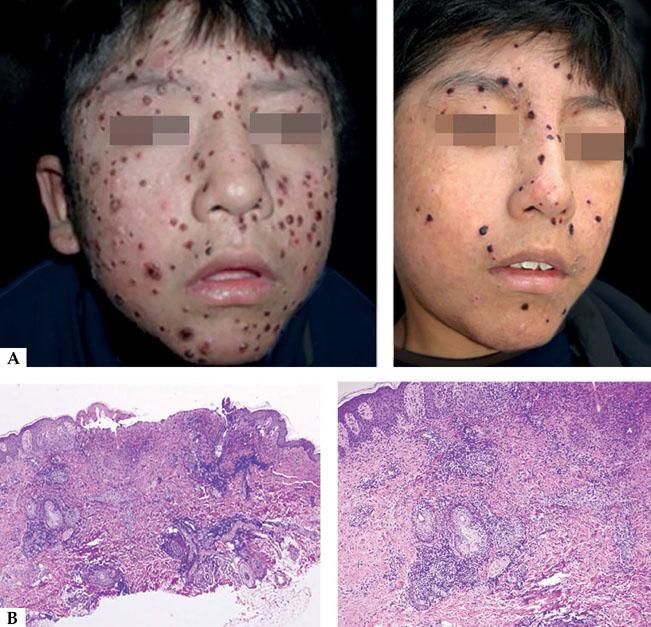

From the clinical point of view, the usual topography of lesions is in photoexposed areas, following this order of frequency: cheeks, ears, nose, hands and forearms.18 Morphologically it is characterized by hemorrhagic vesicles, umbilicated papules settling on an erythematous base, hematic crust that finally evolve to varioliform scars (Figure 3A).13,17 The infrequent clinical manifestations include mucous involvement, as edema and ulcers, in lower lip and on the tip of the tongue, eye manifestations as conjunctivitis, photophobia and corneal ulcers. Scarring of skin lesions can result in bone or cartilage resorption, with the consequent deformities in the hand, pinna or nose (saddle nose).17

A-Clinical aspect of hydroa vacciniforme, with ulcerated lesions leaving depressed scars. In chronic forms, recurrences can occur. B - Histopathology of an acute lesion showing ulceration and a mixed type infiltrate, granulation tissue and infiltrate of large lymphocytes with epithelial and adnexal tropism (Hematoxylin and eosin, x2 and x40)

The atypical or severe forms of HV were reclassified as HV-type lymphoma according to the classification of lymphomas of 2008 of World Health Organization.3Chart 4 shows the differences between HV and HV-type T lymphoma.

The HV differential diagnosis should be made mainly with hepatocutaneous porphyria, erythropoietic protoporphyria, polymorphic light eruption, actinic prurigo and bullous lupus erythematosus. The varioliform scarring of HV allows the distinction with polymorphic light eruption or actinic prurigo. Besides, on actinic prurigo, the itching is usually severe differently from HV where it does not occurs or it occurs in low intensity. In HV, porphyrins values as well in urine as in erythrocytes are normal. The antinuclear antibodies and the direct immunofluorescence are negative.17

Histologically, HV lesions show an epidermal necrosis in varying degrees with a dense infiltrate in papillary and middle dermis with with the presence of lymphocytes with mild atypia and slight epidermotropism (Figure 3B). Most of patients present spontaneous remission of the disease on adult life.3

It was observed that with in situ hybridization techniques it can be found that 3 to 10% of the cells are positive for EBER, which are confirmed by PCR amplification studies. For this reason, it is said that there is a strong evidence of the pathogenic relation between HV and EBV infection.3

Hydroa Vacciniforme-Type T-Cell Lymphoma (HVTL)On the last 20 years in Mexico, Bolivia and Peru, many cases of patients having cutaneous lesions similar to HV were published. At first, they were described as atypical or severe HV, as they later evolved with systemic complications. These cases showed a slow and progressive evolution and finally a complication with malignant lymphoma. Overtime, this entity was identified as a HVTL.

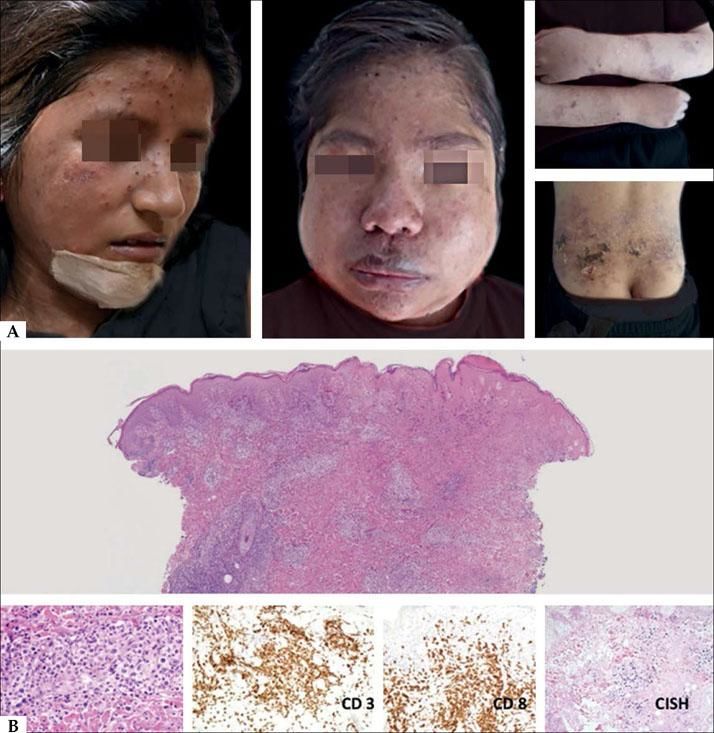

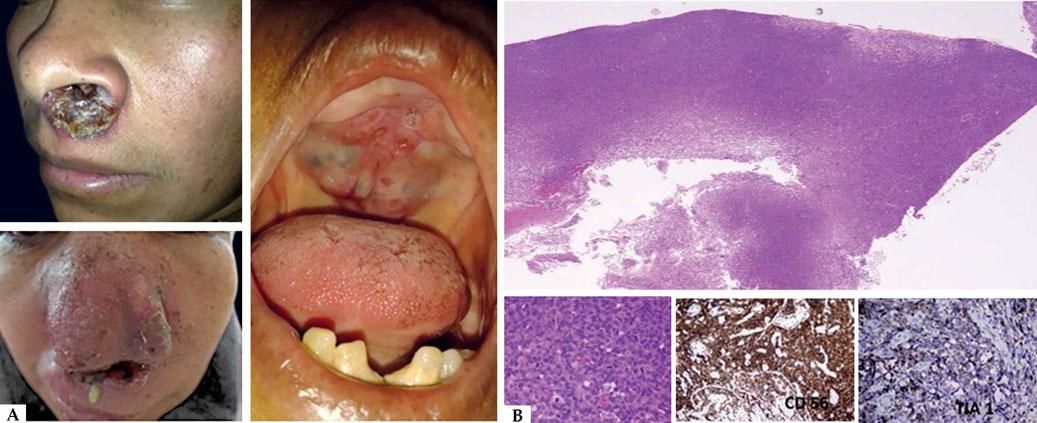

HVTL occurs predominantly in children and adolescents, affects the photoexposed areas mainly in the face and resembles HV.3 These lesions are characterized by the presence of edema, ulcers, blisters, crusts and scars. Differently from HV, these lesions are more extensive and deeper. Extensive scarring and deformity are frequent and the prognosis is reserved. It is often followed by fever, lymphadenopaty, hepatosplenomegaly and increase of hepatic enzymes with a two years survival rate of 36%. Some cases in elderly were reported (Figure 4A).18

A - Clinical aspect of hydroa vacciniforme-type lymphoma: they are infiltrated, ulcerated and edematous lesions. B - Histologically, a nodular infiltrate of atypical cells of medium and large size is observed. The cells are positive for CD3, CD8, and EBV by in situ hybridization (Hematoxylin and eosin, x2 and x40)

From the histological point of view, it is observed a small and average sized T lymphocyte population located in the dermis and hypodermis; sometimes there are marked angiotropism and epidermotropism. When there is an extension to the subcutaneous tissue, it is observed a lobular panniculitis pattern. Immunohistochemically, there is the presence of CD3, CD8 lymphocytes. It is detected the presence of EBV by in situ hybridization method. In tumoral phases, CD56 is found (Figure 4B).

Quintanilla-Martinez et al. reported that 30% of the patients with HVL presented a NK phenotype. The patients with NK phenotype usually present panniculitis lesions with infiltration rich in eosinophils and generally associated with HMB. Morphologically, these lesions can simulate a subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, or or extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma, nasal type, with secondary cutaneous involvement.2 For this reason the clinical differential diagnosis is important.19

The main differential diagnosis is with HV, and especially in early stages, when the presence of large, infiltrated ulcers and associated systemic involvement are striking, findings favoring the HVTL. From the histological point of view, the initial phases have a superficial and deep perivascular pattern with a mixed-type infiltrate, and the presence of atypical cells with enlarged nuclei, irregular chromatin and scarce cytoplasm. In the advanced phase, the infiltrate is more dense and has a mantle pattern; sometimes NK lymphoma is histologically very similar. From the immunohistochemical point of view, it is observed CD56 positivity on tumoral lesions but neither TIA 1 nor perforin. Atypical panniculitis-like forms can be present and, in these cases, the clinical correlation is very important as well as a correct interpretation of the immuno-histochemical findings. (Figure 5A). The lymphoid infiltrate can be found on the deep dermis and hypodermis, for this reason the biopsy must be deep to reach the correct diagnosis (Figure 5B).

A-Atypical presentation forms of hydroa-type lymphoma on eyelids and lips; they present swollen, with ulceration and necrotic areas. B - The infiltrate is dense and diffuse with extension to the hypodermis. At higher magnification, it is identified the presence of atypical cells infiltrating the subcutaneous and muscular tissues (Hematoxylin and eosin, x2 and x40)

NK/T-cell lymphoma is much more frequent in Asia and Latin America (2.6 to 7%) than in United States or Europe (1.5%).20 They are present in two types of population, one young, aged under 20 years old, and another adult, between 50 and 60 years old, predominantly male gender. The survival time is 5 months in average for patients with cutaneous and extracutaneous impairment. In patients presenting only cutaneous impairment, the reported survival time was up to 27 months.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type, is the prototype of NK/T-cell lymphomas associated to EBV. It is a rare aggressive subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma originated in the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses. Typically, they present as a destructive nasal lesion with vascular damage and prominent necrosis, with palate or orbit impairment frequently associated to B symptoms and hemofagocytosis (Figure 6A).21

It can be divided in two subtypes: nasal and extranasal.20 Among the extranasal sites are the skin, the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts and testicle. There is a higher prevalence in Eastern of Asia and Latin America. The histopathological study shows a lymphoid infiltrate of enlarged cells with an irregular chromatin, prominent nucleoli and scarce cytoplasm. These cells present a prominent perivascular pattern and, depending on the stage of the lesion, the infiltrate tends to be more diffuse with large areas of necrosis due to the vascular damage.

The neoplastic cells of the typical cases express CD3, CD8, CD56 and cytotoxic molecules as TIA 1 and granzyme B. Some cases are negative for CD3. Typically, the origin cell is NK cell, but a third of the cases derives from gamma/delta T cells or more rarely alpha/beta T cells.21 EBV is frequently present in the neoplastic cells in the episomal form although there are rare cases of EBV-negative (Figura 6B).20

The diagnosis can be difficult and many biopsies may often be needed to obtain it. The systemic chemotherapy and the bone marrow transplantation seem to be the therapies of choice in this kind of diseases. Nevertheless, regardless of the treatment, the prognosis is poor.

Questions- 1.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is :

- a)

a DNA virus

- b)

a RNA virus

- c)

a picornavirus

- d)

a nanovirus

- a)

- 2.

What is the main entry way of EBV infection?

- a)

gastrointestinal tract

- b)

sexual contact

- c)

blood

- d)

upper respiratory tract

- a)

- 3.

What is the kind of cellular population which primarily mediate the EBV infection?

- a)

Plasma cells

- b)

Monocytes

- c)

CD8+ cytotoxic T cells

- d)

B lymphocytes

- a)

- 4.

Which factors persistence and oncogenic potential of EBV are attributed to?

- a)

Virus capacity to maintain its viral genome in the cells without endangering the life of the host.

- b)

Strategies that allow the evasion of the host immune system.

- c)

Ability to activate cell growth pathways.

- d)

All previous answers.

- a)

- 5.

What is the more frequent neoplasia developed by immunocompromised patients?

- a)

High-grade sarcomas

- b)

Undifferentiated carcinomas

- c)

B lymphomas

- d)

T lymphomas

- a)

- 6.

These are characteristics of latent infection, except:

- a)

To persist in a memory B cell lymphocyte

- b)

The process is controlled by CD8 cytotoxic cells

- c)

Conversion of EBV genome to a circular episome.

- a)

Among almost 100 genes expressed during the replication, only 10 express on latent infection phase.

- a)

- 7.

What is the latency pattern identified with extranodal NK/T lymphomas?

- a)

Latency program type III

- b)

Latency program type I

- c)

Latency program type II a

- d)

Latency program type II b

- a)

- 8.

Which are the diagnostic methods for EBV detection?

- a)

Southern Blot

- b)

PCR

- c)

Immunohistochemistry

- d)

all above

- a)

- 9.

These are infectious mononucleosis features, except:

- a)

non painful enlargement of lymph nodes

- b)

fever during many days

- c)

presence of splenomegaly

- d)

Hydroa vacciniforme

- a)

- 10.

These are characteristics of Lipschutz ulcers, except:

- a)

Deterioration of the general condition and adenomegalies.

- b)

Female patients, under 20 years old.

- c)

Painful kissing ulcers on genital area.

- d)

Positive laboratorial results on the first days of infection.

- a)

Fogo selvagem: pênfigo foliáceo endêmico. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(5):638-50.

1. C

2. A

3. A

4. C

5. B

6. A

7. C

8. D

9. D

10. B