Dear Editor,

Leishmaniasis is an infectious and parasitic disease with a variety of clinical forms, ranging from dermatological lesions (tegumentary leishmaniasis) to systemic manifestations (visceral leishmaniasis).1-4 American tegumentary leishmaniasis (ATL) represents a serious public health problem. Due to the high number of cases of ATL in Brazil, differential diagnosis is necessary to understand the epidemiological profile of ATL, both in areas previously considered non-endemic and in endemic areas. The diagnosis depends on the patient’s clinical history, epidemiology, and laboratory tests.4 Lavras, state of Minas Gerais, had 9 suspected ATL cases reported in the last 7 years, 8 of which were confirmed. Out of them, 7 cases were treated and considered cured, and 1 patient died from treatment-associated toxicity. Furthermore, studies on the phlebotomine fauna evidenced the presence of the main vectors in the municipality. Considering that epidemiological knowledge and clinical characterization of ATL are fundamental precepts of dermatological practices,4 this case report aims to suggest polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as a possible diagnostic tool for cases where the Montenegro antigen is not available and/or histopathological analysis is inconclusive. The PCR is capable of detecting the DNA of parasite in tissue samples in which the parasite forms could not be found.

In 2017, two cases were investigated in Lavras. Case 1 was a 39-year-old female patient who presented with a 5-month history of a lesion on the right arm. Clinical examination revealed a painful ulcer with pruritus measuring 2cm in diameter, with raised, hyperemic, and irregular edges, and central granulation tissue and serous exudate (Figure 1). Due to the unavailability of Montenegro antigen for intradermal reaction, we performed a biopsy to collect lesional specimens. The biopsy was performed after the lesion was cleaned with soap and water and disinfected with ethyl alcohol 70%. We used 2% lidocaine for local anesthesia. Two punch biopsies were taken from the ulcer edge for histopathological analysis, which showed no amastigote forms. The second sample was used for imprint with staining, which also revealed no amastigote forms of the parasite. Subsequently, the same material was preserved in sterile saline solution, macerated with 300μg of extraction buffer, and frozen in a properly identified flask for PCR. After analyzing the electrophoretic pattern of the sample with the positive control, the presence of Leishmania spp. DNA was confirmed.

Case 2 was a 32-year-old female patient who had a lesion on the right thigh since October 2016. She was receiving antibiotic treatment under medical supervision with transient clinical improvement. After 6 months, clinical examination revealed the presence of a painful ulcer of approximately 2cm in diameter with hyperemic edges, and center covered with a meliceric crust (Figure 2). Similarly, as described for case 1, we also performed histopathological analysis and imprint with staining from five different slides and rapid panoptic staining (Romanowsky), also with no identification of amastigote forms of the parasite. After the PCR, the presence of Leishmania spp. DNA was confirmed.

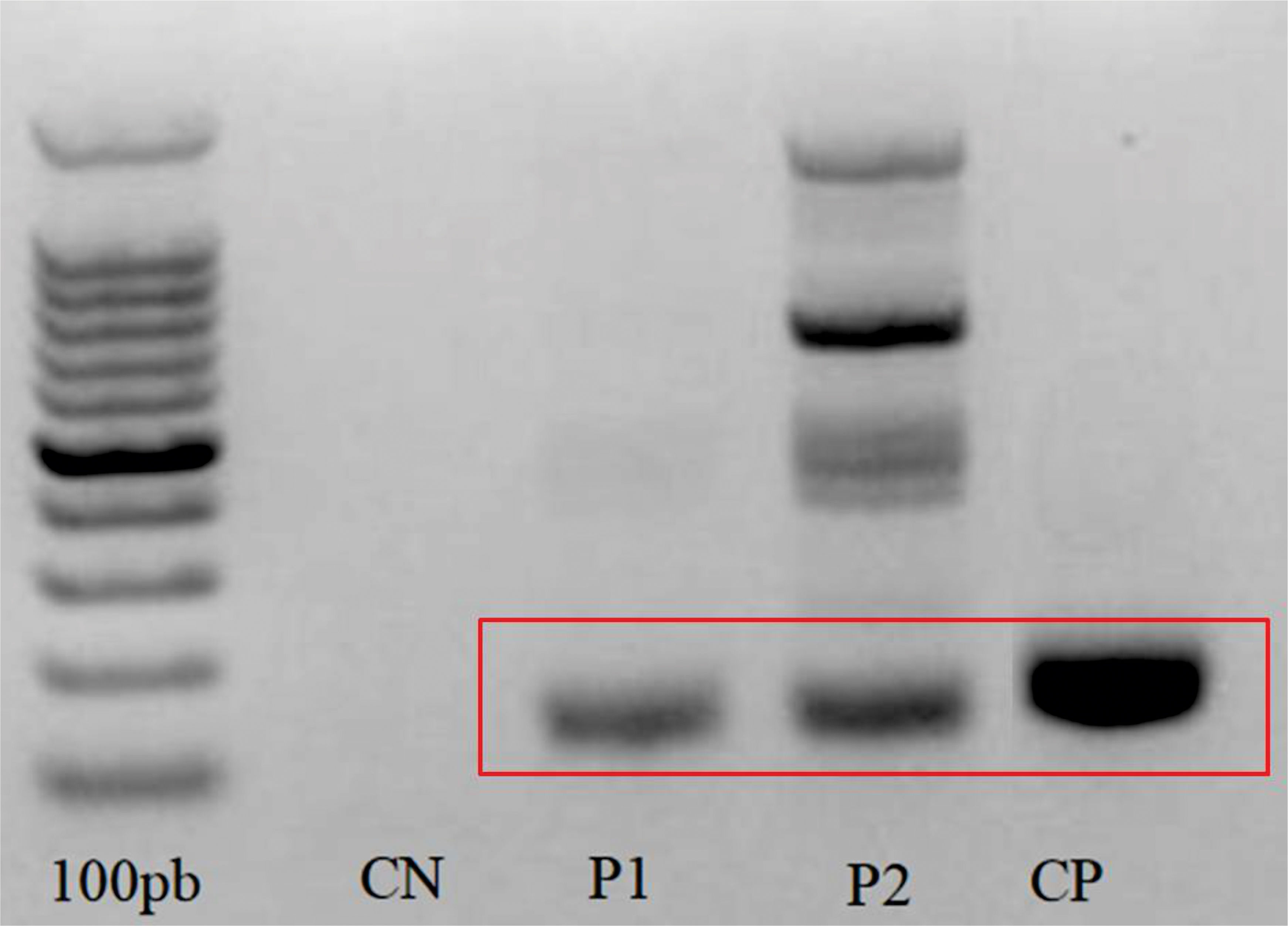

In both cases, after the detection of Leishmania DNA (Figure 3) and diagnostic confirmation of ATL, the treatment chosen was N-methylglucamine antimoniate at a daily intravenous dose of 13.7 ml for 20 days. Both patients evolved to clinical cure after therapy.

Early diagnosis of ATL is a difficult, but essential, task for the clinician, considering the toxicity of the drugs. Since the discovery of Leishmania parasite as causative agents of leishmaniasis, several tests have been developed. However, none of the tests available today can be considered as the gold standard due to the lack of accuracy to detect the disease.5 The present study reports two cases of ATL with diagnosis confirmed by PCR and clinical cure after treatment. These data point to the importance of systematized studies about alternative methodologies to the intradermal Montenegro test, in view of the unavailability of the antigen used.

The authors consider it important to report these cases of ATL with unusual presentation in this municipality and to draw attention to the fact that, although PCR is an exam that is still poorly accessed and expensive, in special situations, it can be very useful. Furthermore, our findings show the importance of continuous health epidemiological surveillance and emphasizes the need for permanent health education to avoid misdiagnosis or underreporting.

Financial Support: FAPEMIG - APQ 02553-14.

Conflict of interest: None.